The afternoon sun filters through the towering ponderosa pines of the Colorado Rockies as a distinctive rustling draws your attention upward. Among the orange-barked giants, a large, dark squirrel with impossibly tufted ears moves with deliberate grace, its magnificent plume-like tail flowing behind like a banner. This is Abert’s Squirrel – the Southwest’s most specialized and arguably most beautiful tree squirrel, a species so intimately tied to ponderosa pine forests that its very survival depends on these majestic trees.

Abert’s Squirrel (Sciurus aberti) is the American Southwest’s ponderosa pine specialist, distinguished by its dramatic ear tufts, large size, and complete dependence on ponderosa pine ecosystems. Unlike the adaptable Fox Squirrel, the forest-generalist Eastern Gray Squirrel, the coastal Douglas Squirrel, or even the territorial American Red Squirrel, Abert’s Squirrels represent extreme ecological specialization, sharing southwestern habitats with the Mexican Fox Squirrel but occupying entirely different ecological niches.

| Attribute | Details |

|---|---|

| Scientific Name | Sciurus aberti |

| Size | 18-23 inches total length |

| Weight | 500-800 grams (1.1-1.8 lbs) |

| Lifespan | 6-10 years wild, up to 15 years maximum |

| Habitat | Ponderosa pine forests, 6,000-9,000 feet elevation |

| Diet | Extreme specialist: ponderosa pine inner bark, seeds, fungi |

| Activity | Diurnal (most active morning and late afternoon) |

| Conservation Status | Near Threatened (habitat dependent) |

Physical Description & Identification

Distinctive Size and Magnificent Appearance

Abert’s Squirrels rank among North America’s most impressive tree squirrels, with a robust build that approaches the size of the largest Fox Squirrels while displaying far more dramatic and distinctive features. Measuring 18-23 inches from nose to tail tip and weighing 500-800 grams, they significantly outsize both the American Red Squirrel and Douglas Squirrel, though they remain slightly smaller than the massive Western Gray Squirrels found in different western ecosystems.

Their substantial build reflects adaptations for life in high-elevation ponderosa pine forests, where larger body size provides advantages for thermal regulation and accessing resources in widely scattered trees. Unlike the compact, energy-efficient builds of smaller territorial species, Abert’s Squirrels display the robust proportions necessary for surviving in challenging montane environments.

The most immediately striking feature of any Abert’s Squirrel is their magnificent tail – a flowing, plume-like appendage that often appears disproportionately large even compared to other bushy-tailed species. This impressive tail serves multiple functions in their specialized mountain forest environment.

Dramatic Ear Tufts and Seasonal Variations

The Iconic Ear Tufts: Perhaps no feature distinguishes Abert’s Squirrels more dramatically than their spectacular ear tufts – long, prominent tufts of black hair that extend well beyond their ears, creating an almost lynx-like appearance unmatched by any other North American tree squirrel. These tufts grow most prominently during winter months, reaching lengths of 1-2 inches and creating one of the most distinctive silhouettes in American wildlife.

Seasonal Coat Changes:

Summer Coat (April-September): Summer pelage displays considerable regional variation, but typically features a grizzled gray to brown dorsal coloration with individual hairs banded in black, white, and brown. The sides often show rusty or reddish-brown tones, while the underside remains white to pale gray. The tail displays dramatic black and white banding that creates a striking contrast visible from considerable distances.

Winter Coat (October-March): Winter pelage grows considerably denser and longer, with enhanced insulation critical for surviving high-elevation winters. The ear tufts reach peak development during winter months, and the overall coloration often becomes more grayish and muted. The magnificent tail becomes even more plume-like, serving as both insulation and a visual display feature.

Regional Color Variations: Across their southwestern range, Abert’s Squirrels display distinct regional color morphs that reflect local adaptations and genetic isolation:

- Kaibab Plateau (Arizona): Pure white tail with dark body (Kaibab Squirrel)

- Colorado Rockies: Classic gray-brown with black and white tail

- New Mexico mountains: More brownish coloration with prominent rusty tones

- Arizona highlands: Variable coloration from gray to reddish-brown

- Utah mountains: Typically grayer with less prominent rusty coloring

Distinguishing Features and Identification

Comparison with Other Large Western Squirrels:

Versus Western Gray Squirrels:

- Ear tufts: Dramatic black tufts vs. no prominent tufts

- Habitat: Ponderosa pine forests vs. oak woodlands

- Tail pattern: Black and white banding vs. silver-gray coloration

- Size: Similar size but different body proportions

- Behavior: More arboreal vs. mixed arboreal-terrestrial

Versus Fox Squirrels:

- Ear tufts: Prominent black tufts vs. no tufts

- Coloration: Gray-brown with white underside vs. variable orange/gray/black

- Habitat specialization: Extreme ponderosa pine specialist vs. habitat generalist

- Geographic range: Southwestern mountains vs. eastern/central North America

- Tail pattern: Distinctive banding vs. solid colors

Unique Physical Adaptations:

- Specialized claws: Enhanced grip for ponderosa pine bark texture

- Powerful jaw muscles: Adapted for processing tough pine bark and needles

- Enhanced cold tolerance: Physiological adaptations for high-elevation winters

- Improved balance: Proportions optimized for navigating large pine branches

- Specialized digestive system: Capable of extracting nutrition from pine tissue

Behavioral Identification:

- Deliberate movements: Slower, more careful locomotion compared to smaller squirrels

- Pine-specific foraging: Distinctive feeding behaviors unique to ponderosa pine

- Seasonal migrations: Elevational movements following resource availability

- Social tolerance: Less territorial aggression than American Red Squirrels

- Distinctive vocalizations: Calls adapted to open ponderosa pine forest environments

Habitat & Distribution

Southwestern Mountain Range Specialization

Abert’s Squirrels occupy one of the most geographically restricted and ecologically specialized ranges among North American tree squirrels, distributed across high-elevation ponderosa pine forests throughout the American Southwest. Their range represents extreme habitat specialization compared to the broad continental distributions of Fox Squirrels or Eastern Gray Squirrels, and even exceeds the specialization of Douglas Squirrels for Pacific Coast forests.

This distribution pattern reflects their evolution as obligate ponderosa pine specialists, making them perhaps the most habitat-specific tree squirrel in North America. Unlike the American Red Squirrel that can utilize various coniferous species, or the Mexican Fox Squirrel that occupies diverse mountain forests, Abert’s Squirrels demonstrate complete dependence on ponderosa pine ecosystems.

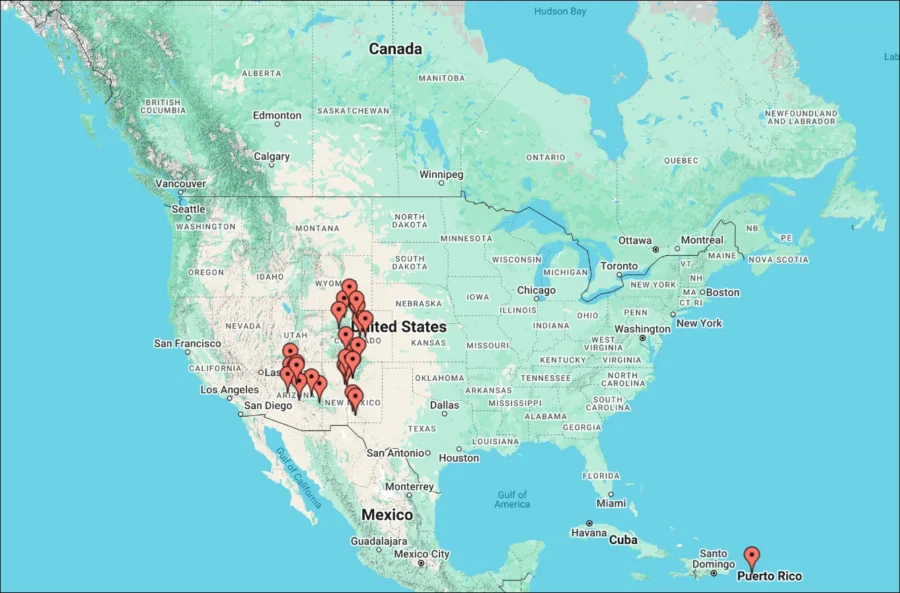

Geographic Distribution:

- Colorado: Front Range and San Juan Mountains

- New Mexico: Sangre de Cristo, Jemez, and Sacramento Mountains

- Arizona: Kaibab Plateau, Coconino Plateau, and White Mountains

- Utah: Limited populations in Wasatch and Uinta Mountains

- Elevation range: 6,000-9,000 feet (optimal 7,000-8,500 feet)

Ponderosa Pine Forest Requirements

Obligate Ponderosa Pine Dependence: Abert’s Squirrels represent one of North America’s most extreme examples of co-evolution between a mammal species and a specific tree species. Their complete dependence on ponderosa pines (Pinus ponderosa) exceeds even the close relationships between Douglas Squirrels and Pacific Coast conifers.

Critical Habitat Characteristics:

- Mature ponderosa pine dominance: Forests with 60-90% ponderosa pine canopy coverage

- Large tree diameter: Preference for trees exceeding 18 inches diameter at breast height

- Open forest structure: Park-like forests with minimal understory density

- Diverse age classes: Mixed mature and old-growth trees providing varied resources

- Adequate connectivity: Forest corridors linking habitat patches

- Minimal human disturbance: Relatively undisturbed forest environments

Optimal Forest Conditions:

- Tree density: 50-150 trees per acre providing optimal spacing

- Canopy coverage: 40-70% coverage allowing understory light penetration

- Understory composition: Grass and forb communities with minimal shrub density

- Topographic diversity: Varied terrain providing microclimatic diversity

- Water availability: Seasonal streams or springs within foraging range

- Fire history: Forests with natural fire regimes maintaining open structure

Elevation and Climate Adaptations

High-Elevation Specialization: Abert’s Squirrels have evolved remarkable adaptations for life in high-elevation environments that present challenges unknown to lower-elevation species like Eastern Gray Squirrels or the Fox Squirrels found in temperate regions.

Montane Environment Adaptations:

- Cold tolerance: Enhanced physiological adaptations for sub-zero temperatures

- Seasonal resource management: Behavioral strategies for surviving resource-scarce periods

- Altitude physiology: Enhanced oxygen extraction efficiency for high-elevation environments

- Snow navigation: Behavioral adaptations for deep snow conditions

- UV protection: Physiological protections against intense high-altitude solar radiation

Climatic Requirements:

- Annual precipitation: 20-35 inches, primarily winter snow and summer monsoons

- Temperature range: Summer highs 70-80°F, winter lows -10 to 10°F

- Growing season: 120-180 frost-free days supporting ponderosa pine growth

- Seasonal patterns: Distinct winter and summer seasons with spring/fall transitions

- Storm tolerance: Ability to survive intense mountain weather systems

Regional Population Variations and Subspecies

Kaibab Squirrel (Sciurus aberti kaibabensis): The most distinctive Abert’s Squirrel population inhabits Arizona’s Kaibab Plateau, displaying unique characteristics that distinguish them from all other southwestern populations and represent one of North America’s most remarkable examples of geographic isolation effects.

Kaibab Plateau Specializations:

- Pure white tail: Completely white tail contrasting with dark body

- Enhanced ear tufts: Larger, more prominent tufts than other populations

- Isolated evolution: Genetic isolation creating unique characteristics

- Habitat specificity: Dependence on specific Kaibab Plateau ponderosa pine forests

- Conservation significance: Small, isolated population requiring special protection

Regional Adaptations Across Range:

- Colorado populations: Largest body size and most robust build

- New Mexico populations: Intermediate characteristics with brownish coloration

- Arizona populations: Variable characteristics including the unique Kaibab form

- Utah populations: Smallest and most peripheral populations

- Elevation effects: Higher elevation populations showing enhanced cold adaptations

Population Connectivity and Isolation:

- Habitat fragmentation: Separated populations in isolated mountain ranges

- Gene flow limitations: Restricted movement between population centers

- Local adaptations: Population-specific characteristics reflecting local conditions

- Conservation implications: Isolated populations vulnerable to local extinctions

- Management challenges: Need for landscape-scale conservation approaches

Diet & Feeding Behavior

Extreme Ponderosa Pine Specialization

Abert’s Squirrels display the most specialized diet of any North American tree squirrel, with feeding behaviors completely adapted to ponderosa pine ecosystems. Their dietary specialization exceeds even that of Douglas Squirrels for Pacific Coast conifers or American Red Squirrels for boreal forest resources, representing one of the most extreme examples of co-evolutionary adaptation in North American mammals.

Unlike the dietary flexibility that allows Fox Squirrels and Eastern Gray Squirrels to thrive in diverse environments, Abert’s Squirrels have evolved to extract virtually all their nutritional needs from ponderosa pines and their associated forest communities.

Seasonal Dietary Patterns:

Spring Diet (March-May):

- Ponderosa pine inner bark (phloem): Primary food source providing essential carbohydrates

- Fresh pine needles: Young growth providing vitamins and minerals

- Pine pollen: Protein-rich reproductive structures during peak production

- Emerging fungi: Early spring mushrooms associated with pine root systems

- Tree buds: Growing points from ponderosa pines and occasional associated trees

- Limited supplements: Occasional consumption of other available vegetation

Summer Diet (June-August):

- Continued inner bark consumption: Year-round reliance on ponderosa pine phloem

- Developing pine cones: Immature cones before seed development

- Diverse fungi: Peak mushroom season with species associated with pine forests

- Pine needle selection: Seasonal variation in needle age preferences

- Supplemental vegetation: Limited consumption of grasses and forbs

- Hypogeous fungi: Underground mushrooms accessed through digging

Autumn Diet (September-November):

- Peak cone consumption: Mature ponderosa pine seeds when available

- Inner bark intensification: Increased phloem consumption preparing for winter

- Late-season fungi: Autumn mushroom species extending fungal foraging

- Seed storage: Limited caching of pine seeds for winter use

- Bark stockpiling: Behavioral preparation for winter resource needs

- Nutritional optimization: Increased caloric intake before winter scarcity

Winter Diet (December-February):

- Primary phloem dependence: Heavy reliance on ponderosa pine inner bark

- Cached resources: Limited use of stored pine seeds and bark

- Needle consumption: Continued consumption of pine needles for nutrition

- Reduced activity: Energy conservation minimizing metabolic demands

- Opportunistic feeding: Limited consumption of available winter resources

- Survival mode: Minimal dietary diversity focusing on available pine resources

Ponderosa Pine Bark Processing Techniques

Abert’s Squirrels have evolved sophisticated techniques for accessing and processing ponderosa pine inner bark (phloem), representing feeding behaviors completely unique among North American tree squirrels and unknown among the more generalized feeding strategies of Fox Squirrels or Eastern Gray Squirrels.

Bark Access and Processing:

- Selective tree choice: Preference for specific ponderosa pines based on bark characteristics

- Optimal branch selection: Targeting terminal branches with tender bark

- Systematic stripping: Methodical removal of outer bark to access phloem layer

- Quality assessment: Ability to evaluate nutritional content before extensive processing

- Seasonal timing: Bark processing synchronized with phloem sugar content

Specialized Feeding Techniques:

- Precise gnawing: Surgical removal of bark without damaging cambium layer

- Strip patterns: Distinctive spiral or linear patterns of bark removal

- Branch selection: Preference for 0.5-2 inch diameter branches

- Height preferences: Feeding concentrated in upper canopy areas

- Tree rotation: Systematic use of multiple trees within territory

Digestive Adaptations:

- Enhanced gut bacteria: Specialized microorganisms processing cellulose and lignin

- Extended gut length: Anatomical adaptations maximizing nutrient extraction

- Seasonal digestive changes: Physiological adjustments accommodating dietary shifts

- Efficient processing: Behavioral techniques maximizing nutritional extraction

- Waste minimization: Digestive efficiency reducing energy expenditure

Mycorrhizal Fungi Relationships

Abert’s Squirrels have developed sophisticated relationships with mycorrhizal fungi that form symbiotic associations with ponderosa pine root systems, creating ecological relationships of complexity unknown among other North American squirrel species including the American Red Squirrel or Douglas Squirrel.

Fungal Foraging Strategies:

- Species recognition: Ability to identify valuable mycorrhizal fungi species

- Seasonal timing: Coordinated foraging with fungal reproductive cycles

- Habitat assessment: Understanding of optimal fungal growth locations

- Harvest techniques: Careful extraction methods preserving fungal networks

- Processing methods: Preparation techniques optimizing nutritional value

Ecological Significance:

- Spore dispersal: Abert’s Squirrels serve as primary dispersal agents for mycorrhizal fungi

- Forest health support: Fungal dispersal supporting ponderosa pine forest ecosystems

- Nutrient cycling: Participation in forest nutrient distribution systems

- Symbiotic relationships: Three-way mutualism between squirrels, fungi, and trees

- Ecosystem engineering: Behavioral activities supporting forest community structure

Fungal Processing and Storage:

- Fresh consumption: Immediate consumption of highest-quality specimens

- Drying techniques: Limited preparation of fungi for short-term storage

- Quality evaluation: Ability to assess nutritional and safety characteristics

- Seasonal integration: Incorporation of fungi into year-round dietary strategies

- Digestive specialization: Physiological adaptations for processing fungal tissues

Territory and Resource Management

Unlike the intensive territorial systems of American Red Squirrels or Douglas Squirrels, Abert’s Squirrels maintain more flexible territory systems adapted to the patchy distribution of optimal ponderosa pine resources and the challenges of high-elevation environments.

Territory Characteristics:

- Large territory size: 5-25 acres depending on habitat quality and resource density

- Flexible boundaries: Territory size and shape varying with seasonal resource availability

- Resource-based territories: Territory organization centered on high-quality ponderosa pine groves

- Seasonal adjustments: Territory modifications based on food availability and weather conditions

- Social tolerance: Higher tolerance for neighboring squirrels compared to smaller territorial species

Resource Management Strategies:

- Tree selection: Preference for specific ponderosa pines with optimal bark characteristics

- Sustainable harvesting: Bark removal patterns allowing tree survival and regrowth

- Multiple resource trees: Utilization of numerous trees within territory reducing individual tree stress

- Seasonal rotation: Strategic use of different trees based on seasonal resource quality

- Conservation behaviors: Feeding patterns supporting long-term resource availability

Home Range Utilization:

- Core areas: Intensive use areas containing optimal resource concentrations

- Travel corridors: Regular routes connecting resource patches and shelter sites

- Seasonal ranges: Different area utilization based on resource availability and weather

- Elevation migrations: Movement patterns following optimal conditions and resources

- Shelter site distribution: Multiple nest locations throughout territory for various conditions

Reproduction & Life Cycle

High-Elevation Breeding Adaptations

Abert’s Squirrels experience a single annual breeding season precisely timed to southwestern mountain climate patterns and the unique challenges of high-elevation ponderosa pine environments. Their reproductive strategy reflects adaptations to harsh winter conditions and the seasonal resource availability patterns that differ dramatically from the environments inhabited by Eastern Gray Squirrels, Fox Squirrels, or even the mountain-adapted American Red Squirrels.

Primary Breeding Season (February-April): Abert’s Squirrel breeding occurs during late winter and early spring, synchronized with high-elevation snowmelt and the beginning of optimal resource availability periods in ponderosa pine forests.

High-Elevation Breeding Challenges:

- Harsh winter conditions: Breeding during periods of snow cover and cold temperatures

- Resource limitations: Mating during periods of limited food availability

- Weather unpredictability: Mountain weather extremes affecting reproductive success

- Predator pressure: Increased vulnerability during courtship activities

- Energy conservation: Breeding strategies minimizing energy expenditure

Geographic and Elevational Breeding Variations:

- Southern populations (Arizona/New Mexico): Earlier breeding due to warmer conditions

- Northern populations (Colorado/Utah): Later breeding adapted to extended winter periods

- High elevation sites: Delayed breeding based on snowpack and temperature patterns

- Protected valleys: Modified timing in sheltered microclimates

- Aspect influences: Breeding timing varying with slope orientation and solar exposure

Courtship in Ponderosa Pine Forests

Abert’s Squirrel courtship involves behaviors adapted to the open structure of ponderosa pine forests and the challenges of locating potential mates across large territories in mountainous terrain, creating courtship patterns distinct from the intensive territorial competitions of Douglas Squirrels or the more flexible social systems of Fox Squirrels.

Pre-Mating Behaviors:

- Long-distance calling: Vocalizations adapted to carry across open ponderosa pine forests

- Scent trail marking: Chemical communication spanning large mountainous territories

- Visual displays: Tail flagging and body positioning visible across forest openings

- Territory expansion: Males temporarily enlarging territories to access potential mates

- Competitive interactions: Male-male competition for access to receptive females

Mating Process: Female Abert’s Squirrels typically mate with multiple males during their receptive period, which lasts 6-10 hours, ensuring genetic diversity while allowing assessment of male quality through behavioral displays and competitive success.

Courtship Communication:

- Forest-adapted vocalizations: Calls optimized for open forest acoustics

- Visual signaling: Long-distance communication using distinctive ear tufts and tail displays

- Scent communication: Chemical signals utilizing mountain air currents

- Physical demonstrations: Agility and strength displays showcasing male fitness

- Territory quality assessment: Female evaluation of male territory resources and protection

Nest Site Selection in Mountain Environments

Gestation Period: 40-44 days

Nest Site Requirements: Abert’s Squirrels face unique challenges in selecting nest sites within ponderosa pine forests, requiring protection from mountain weather extremes while providing access to essential resources, creating nesting requirements different from those of Eastern Gray Squirrels in temperate forests or Douglas Squirrels in coastal environments.

Natural Cavity Utilization:

- Ponderosa pine cavities: Natural hollows in mature pine trees

- Snag utilization: Dead trees providing cavity opportunities

- Woodpecker holes: Modified cavities in large-diameter pines

- Bark pocket formations: Natural cavities created by bark structure

- Rock crevices: Alternative sites in rocky mountain terrain

Drey Construction Techniques:

- Wind-resistant design: Construction methods adapted to mountain wind conditions

- Thermal insulation: Building techniques optimizing warmth retention

- Weather protection: Nest positioning and materials providing storm protection

- Multiple nest sites: Seasonal and backup nests throughout territory

- Elevation considerations: Nest placement optimizing sun exposure and protection

Construction Materials:

- Ponderosa pine materials: Needles, bark strips, and small branches

- Insulation materials: Moss, lichen, and soft plant materials

- Regional adaptations: Use of locally available mountain forest materials

- Seasonal materials: Different materials utilized based on availability

- Weather resistance: Material selection for mountain climate durability

Offspring Development and Mountain Adaptations

Birth Characteristics: Abert’s Squirrel litters typically contain 2-4 young, born after the 40-44 day gestation period, with development patterns adapted to high-elevation environmental challenges and the specialized requirements of ponderosa pine forest survival.

Newborn Features:

- Size: Approximately 3.5 inches long, weighing 12-16 grams

- Appearance: Pink, hairless, with closed eyes and ears

- Development: Moderate maturation rate balancing size requirements with environmental pressures

Developmental Timeline:

Weeks 1-3:

- Rapid initial growth: Fast weight gain through rich maternal milk

- Thermoregulation dependence: Critical warmth requirements in mountain climates

- First hair development: Beginning of distinctive Abert’s Squirrel characteristics

Weeks 4-5:

- Eye opening: Eyes open around day 26-30

- Hearing development: Ear function beginning around day 28-32

- Motor coordination: Initial balance and movement development

- Nest exploration: Short ventures within nest cavity or drey

Weeks 6-7:

- First emergence: Initial exploration outside nest in ponderosa pine environment

- Ear tuft development: Beginning growth of characteristic ear tufts

- Solid food introduction: First exposure to pine bark and other foods

- Climbing instruction: Maternal teaching of ponderosa pine navigation

Weeks 8-10:

- Weaning progression: Gradual reduction of nursing dependency

- Foraging education: Learning ponderosa pine bark processing techniques

- Territory exploration: Guided tours of mountain territory features

- Predator awareness: Education about mountain threats and escape strategies

Weeks 11-14:

- Independence preparation: Extended time developing survival skills

- Specialized skill development: Advanced bark processing and fungal identification

- Mountain navigation: Learning elevation-based movement patterns

- Winter preparation: Education about surviving high-elevation winters

Weeks 15-18:

- Dispersal readiness: Preparation for establishing individual territories

- Adult behavior development: Full expression of Abert’s Squirrel characteristics

- Social skills: Understanding of population density and territorial systems

- Survival competency: Ability to survive independently in ponderosa pine forests

Extended Maternal Investment: Abert’s Squirrel mothers provide exceptionally long and intensive parental care, including detailed instruction in the specialized techniques required for surviving as ponderosa pine specialists in challenging high-elevation environments.

Behavior & Social Structure

Social Systems in Open Mountain Forests

Abert’s Squirrels maintain social systems that differ markedly from the intensive territorial behaviors of American Red Squirrels and Douglas Squirrels, while showing less flexibility than the adaptable social structures of Fox Squirrels and Eastern Gray Squirrels. Their social organization reflects adaptation to the patchy distribution of ponderosa pine resources and the challenges of high-elevation mountain environments.

Territory and Home Range Systems:

- Large, flexible territories: Territory sizes varying from 5-25 acres based on habitat quality

- Resource-based boundaries: Territory organization following optimal ponderosa pine distributions

- Seasonal territory adjustments: Boundary modifications based on resource availability and weather

- Overlapping ranges: Tolerance for territory overlap during resource abundance periods

- Social hierarchies: Dominance systems based on territory quality and individual condition

Social Tolerance and Cooperation:

- Reduced aggression: Less territorial intensity compared to smaller specialized squirrels

- Resource sharing: Limited tolerance for sharing high-quality feeding areas

- Information networks: Indirect communication about predators and environmental conditions

- Seasonal aggregations: Temporary gathering in optimal habitat areas

- Neighbor recognition: Stable relationships with adjacent territory holders

Population Density Management:

- Self-regulating mechanisms: Behavioral adaptations preventing habitat overuse

- Dispersal patterns: Young squirrel movement maintaining population distribution

- Habitat quality assessment: Population density correlating with ponderosa pine forest condition

- Stress responses: Behavioral changes during high-density periods

- Resource competition: Competitive interactions intensifying during scarcity periods

Communication Adapted to Mountain Forests

Abert’s Squirrels have evolved communication systems specifically adapted to the acoustic properties of open ponderosa pine forests and the challenges of long-distance communication across mountainous terrain, creating vocalizations and signaling behaviors distinct from those of other North American squirrel species.

Vocal Communication Systems:

Long-Distance Forest Calls:

- Territorial calls: Low-frequency vocalizations carrying across open forest structures

- Contact calls: Moderate-frequency sounds maintaining social connections

- Alarm calls: Sharp, penetrating warnings for predator threats

- Courtship vocalizations: Specialized calls during breeding season interactions

Acoustic Adaptations:

- Frequency optimization: Vocal frequencies minimizing interference from wind and forest sounds

- Call duration: Extended vocalizations improving transmission across distances

- Repetition patterns: Call sequences enhancing message clarity and reception

- Directional calling: Vocal techniques utilizing forest acoustics for sound projection

Visual Communication:

- Ear tuft displays: Dramatic ear tuft positioning communicating emotional states

- Tail signaling: Elaborate tail movements visible across forest openings

- Body posturing: Position and movement patterns conveying dominance and intent

- Seasonal visual changes: Enhanced visual displays during breeding season

Chemical Communication:

- Scent marking: Strategic placement of chemical signals on prominent trees

- Territory marking: Scent boundaries adapted to large territory systems

- Individual recognition: Unique scent signatures facilitating neighbor identification

- Reproductive signaling: Chemical communication during breeding season

Daily Activity Patterns in Mountain Environments

Abert’s Squirrels have adapted their daily routines to high-elevation mountain conditions, including extreme temperature variations, intense solar radiation, and seasonal weather patterns that create activity schedules different from those of squirrels in more temperate environments.

Typical Mountain Daily Schedule:

Dawn Activity (Sunrise + 1 hour to Mid-Morning):

- Temperature optimization: Activity beginning after overnight cold periods

- Feeding concentration: Intensive foraging during optimal temperature conditions

- Territory patrol: Morning inspection of territory boundaries and resources

- Social interactions: Brief encounters with neighboring individuals

Midday Behavior (Late Morning to Mid-Afternoon):

- Thermal regulation: Seeking shade during intense mountain sun exposure

- Rest periods: Energy conservation during peak heat and UV radiation

- Grooming activities: Coat maintenance and parasite management

- Cache organization: Limited food storage and territory maintenance

Evening Activity (Late Afternoon to Sunset):

- Final foraging: Intensive feeding before overnight temperature drops

- Nest preparation: Evening shelter preparation for mountain nights

- Social signaling: Vocal communication and territory reinforcement

- Predator vigilance: Increased awareness during predator activity periods

Seasonal Activity Modifications:

- Winter: Dramatically reduced activity with increased shelter use

- Spring: Extended activity during breeding season and resource abundance

- Summer: Activity patterns avoiding midday heat and UV exposure

- Autumn: Intensive foraging preparing for winter resource limitations

Elevational Migration and Seasonal Movements

Unlike most North American tree squirrels, including Fox Squirrels and Eastern Gray Squirrels that maintain relatively stable territories, Abert’s Squirrels often undertake seasonal elevational migrations following optimal conditions and resource availability within mountain ponderosa pine ecosystems.

Seasonal Movement Patterns:

- Winter descent: Movement to lower elevations during harsh winter conditions

- Spring ascent: Return to higher elevations following snowmelt and warming

- Resource tracking: Movements following optimal ponderosa pine condition cycles

- Weather avoidance: Temporary relocations during severe mountain storms

- Breeding migrations: Movement patterns during courtship and mating periods

Migration Triggers:

- Snow depth: Deep snow prompting movement to more accessible areas

- Temperature extremes: Severe cold driving elevational descent

- Resource availability: Food scarcity triggering territory abandonment

- Social factors: Population density influencing movement decisions

- Predator pressure: Increased threats prompting temporary relocations

Habitat Connectivity Requirements:

- Forest corridors: Continuous ponderosa pine habitat enabling safe movement

- Elevation gradients: Habitat availability across elevation zones

- Shelter availability: Adequate nest sites supporting temporary occupancy

- Resource distribution: Food sources available along migration routes

- Reduced human disturbance: Movement corridors free from excessive human activity

Interaction with Humans and Conservation Challenges

Mountain Recreation and Human Impacts

Abert’s Squirrels face unique human-wildlife interaction challenges within their high-elevation ponderosa pine habitats, particularly from increasing mountain recreation activities, forest management practices, and climate change impacts that differ significantly from the urban adaptation challenges faced by Fox Squirrels and Eastern Gray Squirrels.

Recreation Impact Factors:

- Hiking and camping: Human presence disrupting natural behavior patterns

- Mountain biking: Trail activities fragmenting habitat and causing disturbance

- Rock climbing: Activities affecting cliff-associated habitat areas

- Off-road vehicle use: Habitat damage and noise disturbance

- Seasonal recreation pressure: Intensive human use during optimal squirrel activity periods

Forest Management Conflicts:

- Logging activities: Removal of mature ponderosa pines essential for survival

- Fire management: Suppression altering natural forest structure and composition

- Road construction: Habitat fragmentation and barrier creation

- Utility corridors: Forest clearing for power lines and infrastructure

- Grazing impacts: Livestock affecting understory conditions and forest regeneration

Climate Change Vulnerabilities:

- Temperature increases: Warming affecting high-elevation habitat suitability

- Precipitation changes: Altered snowpack and monsoon patterns affecting forest health

- Fire regime changes: Increased wildfire frequency and intensity

- Pest outbreaks: Climate-driven insect problems affecting ponderosa pine forests

- Elevational shifts: Suitable habitat moving upward beyond available mountain terrain

Human-Abert’s Squirrel Conflict Resolution

Unlike the common building invasion issues seen with Eastern Gray Squirrels or garden conflicts with Fox Squirrels, Abert’s Squirrel conflicts typically center on habitat protection and recreation management rather than direct property damage.

Primary Conflict Types:

- Habitat disturbance: Human activities disrupting essential ponderosa pine forests

- Recreation conflicts: Hiking, camping, and recreational activities affecting squirrel behavior

- Forest management disputes: Logging and forest treatment impacts on critical habitat

- Development pressure: Expansion of human infrastructure into squirrel habitat

- Research disturbance: Scientific activities potentially affecting sensitive populations

Mountain Community Coexistence:

- Education programs: Public awareness about Abert’s Squirrel habitat needs

- Recreation guidelines: Visitor education about wildlife-friendly practices

- Seasonal restrictions: Limiting human activities during critical periods

- Habitat protection: Community support for conservation measures

- Monitoring cooperation: Citizen involvement in population assessment

Forest Management Collaboration:

- Habitat-sensitive logging: Timber practices preserving essential squirrel resources

- Fire management planning: Prescribed burns maintaining natural forest structure

- Road planning: Infrastructure development minimizing habitat fragmentation

- Restoration projects: Collaborative efforts restoring degraded ponderosa pine forests

- Research partnerships: Cooperative studies informing management decisions

Conservation Education and Awareness

Public Education Priorities:

- Habitat specialization: Understanding Abert’s Squirrel dependence on ponderosa pine forests

- Conservation importance: Recognizing their role as indicator species for forest health

- Threat awareness: Education about habitat loss and fragmentation impacts

- Coexistence strategies: Promoting human activities compatible with squirrel conservation

- Research support: Encouraging participation in citizen science and monitoring

Educational Opportunities:

- Wildlife observation: Responsible viewing practices in ponderosa pine forests

- Photography ethics: Guidelines for minimizing disturbance during documentation

- Habitat interpretation: Understanding forest ecology and squirrel relationships

- Conservation messaging: Communicating conservation needs to broader audiences

- School programs: Environmental education featuring southwestern mountain ecosystems

Community Engagement:

- Volunteer monitoring: Citizen science participation in population surveys

- Habitat restoration: Community involvement in forest improvement projects

- Advocacy training: Educating supporters about conservation policy needs

- Fundraising support: Community-based conservation funding initiatives

- Tourism development: Sustainable wildlife viewing promoting conservation awareness

Conservation Status and Management Priorities

Population Status and Threat Assessment

Abert’s Squirrels face significantly greater conservation challenges than the stable populations of Fox Squirrels and Eastern Gray Squirrels, with their extreme habitat specialization making them vulnerable to environmental changes that would have minimal impact on more adaptable species.

Current Conservation Status:

- Overall classification: Near Threatened with declining trend

- Kaibab Squirrel subspecies: Critically vulnerable due to isolation

- Population fragmentation: Isolated populations in separated mountain ranges

- Habitat dependency: Complete reliance on ponderosa pine forest ecosystems

- Climate vulnerability: High sensitivity to environmental changes

Regional Population Status:

- Colorado: Largest and most stable populations

- Arizona: Variable populations with the unique Kaibab subspecies

- New Mexico: Moderate populations facing habitat pressure

- Utah: Small, peripheral populations at risk

- Overall trend: Declining in southern range, stable in northern areas

Primary Threat Categories:

- Habitat loss: Logging and development reducing available ponderosa pine forests

- Forest fragmentation: Road construction and development breaking up habitat continuity

- Climate change: Warming temperatures affecting high-elevation forest composition

- Fire regime changes: Altered fire patterns affecting forest structure

- Recreation pressure: Increasing human use of mountain forest environments

Specialized Conservation Needs

Ponderosa Pine Forest Management:

- Old-growth protection: Preserving mature trees essential for Abert’s Squirrel survival

- Forest restoration: Reestablishing natural ponderosa pine forest structure

- Fire management: Using prescribed burns to maintain open forest conditions

- Sustainable logging: Timber practices maintaining habitat while allowing forest use

- Connectivity preservation: Maintaining corridors between forest patches

Population Management:

- Genetic diversity: Protecting gene flow between isolated populations

- Population monitoring: Regular surveys tracking population trends and health

- Translocation programs: Moving individuals to restore depleted populations

- Habitat enhancement: Improving forest conditions to support larger populations

- Research priorities: Studies informing effective conservation strategies

Climate Adaptation Planning:

- Assisted migration: Potential translocation to suitable habitats at higher elevations

- Habitat corridor development: Creating connections for natural range shifts

- Forest adaptation: Management helping ponderosa pine forests adapt to climate change

- Monitoring programs: Tracking climate impacts on squirrel populations

- Adaptive management: Flexible strategies responding to changing conditions

Research and Management Priorities

Critical Research Needs:

- Population genetics: Understanding genetic diversity and population connectivity

- Habitat requirements: Detailed studies of optimal forest conditions

- Climate impacts: Research on temperature and precipitation effects

- Behavioral ecology: Studies of feeding, reproduction, and territorial behavior

- Forest management effects: Evaluation of logging and fire management impacts

Conservation Partnerships:

- Federal agencies: Collaboration with Forest Service and National Park Service

- State wildlife agencies: Coordination with state conservation departments

- Research institutions: University partnerships supporting scientific studies

- Conservation organizations: NGO involvement in habitat protection

- Private landowners: Cooperation with forest landowners for habitat conservation

Management Tools:

- Habitat modeling: GIS analysis identifying priority conservation areas

- Population viability analysis: Assessing long-term survival probabilities

- Forest management guidelines: Best practices for maintaining squirrel habitat

- Monitoring protocols: Standardized methods for tracking population trends

- Conservation planning: Landscape-scale strategies protecting habitat networks

How to Help Abert’s Squirrels

Creating and Protecting Ponderosa Pine Habitat

Property owners and land managers within Abert’s Squirrel range can take specific actions supporting conservation while recognizing that habitat requirements differ dramatically from those needed by more adaptable species like Fox Squirrels or Eastern Gray Squirrels.

Ponderosa Pine Forest Management:

Tree Selection and Maintenance:

- Mature ponderosa pine preservation: Protecting existing large-diameter trees

- Diverse age class maintenance: Managing forests with varied tree ages

- Selective thinning: Removing competing species while preserving pines

- Natural regeneration support: Allowing ponderosa pine reproduction

- Cavity tree retention: Preserving trees with natural hollows when safe

Forest Structure Optimization:

- Open understory maintenance: Managing for park-like forest conditions

- Fire management: Using prescribed burns to maintain natural forest structure

- Invasive species control: Removing non-native plants competing with native vegetation

- Grazing management: Controlling livestock impacts on forest regeneration

- Erosion prevention: Protecting soil resources supporting tree health

Habitat Connectivity:

- Corridor preservation: Maintaining forest connections between habitat patches

- Edge management: Creating gradual transitions between forest and open areas

- Elevation diversity: Protecting habitat across elevation gradients

- Seasonal habitat: Ensuring year-round resource availability

- Movement facilitation: Reducing barriers to squirrel movement

Mountain Property Management for Conservation

Sustainable Forest Practices:

- Chemical-free management: Avoiding pesticides and herbicides affecting forest ecosystems

- Native species emphasis: Focusing on plants supporting ponderosa pine forest communities

- Organic soil management: Using natural amendments supporting tree health

- Integrated ecosystem management: Approaches supporting entire forest communities

- Natural process restoration: Reestablishing natural forest dynamics

Infrastructure and Development:

- Minimal impact development: Building practices reducing habitat disturbance

- Road planning: Minimizing forest fragmentation from access routes

- Utility placement: Strategically locating power lines and infrastructure

- Recreation management: Controlling human activities to minimize wildlife disturbance

- Seasonal restrictions: Limiting activities during critical periods

Water and Microclimate Management:

- Natural hydrology: Maintaining natural water flow patterns

- Spring protection: Preserving water sources essential for forest health

- Microclimate preservation: Protecting diverse temperature and moisture zones

- Wind protection: Maintaining forest structure providing shelter

- Erosion control: Preventing soil loss affecting forest productivity

Supporting Abert’s Squirrel Research and Conservation

Citizen Science Participation:

- Population monitoring: Contributing to annual Abert’s Squirrel surveys

- Behavioral documentation: Recording observations of feeding, nesting, and social behaviors

- Habitat assessment: Documenting forest conditions and changes over time

- Distribution mapping: Contributing sighting data expanding knowledge of current range

Research Support:

- University partnerships: Supporting graduate research on Abert’s Squirrel ecology

- Conservation organization funding: Donating to groups working on southwestern conservation

- Property access: Allowing researchers to conduct studies on private forest lands

- Data collection: Assisting with field work and long-term monitoring efforts

Conservation Advocacy:

- Policy support: Advocating for Abert’s Squirrel habitat protection in forest planning

- Education outreach: Sharing knowledge about conservation needs with communities

- Sustainable tourism: Promoting responsible wildlife viewing in ponderosa pine forests

- Conservation funding: Supporting habitat protection and restoration projects

Forest Landowner Recommendations

Sustainable Forestry for Abert’s Squirrels:

- Habitat-sensitive logging: Timber practices preserving essential squirrel resources

- Retention forestry: Leaving critical trees and habitat features during operations

- Long-term planning: Forest management supporting continuous habitat availability

- Ecosystem service recognition: Understanding Abert’s Squirrel contributions to forest health

Economic Incentive Programs:

- Conservation easements: Financial incentives for protecting critical ponderosa pine habitat

- Forest certification: Programs rewarding wildlife-friendly forest management

- Cost-sharing assistance: Government programs supporting habitat enhancement

- Tax incentives: Benefits for maintaining essential Abert’s Squirrel habitat

Collaborative Conservation:

- Neighbor coordination: Working with adjacent landowners for landscape-scale conservation

- Agency partnerships: Collaborating with forest service and wildlife agencies

- Research cooperation: Supporting scientific studies on forest management effects

- Adaptive management: Flexible approaches responding to new conservation information

Conclusion

Abert’s Squirrel represents one of North America’s most remarkable examples of ecological specialization and co-evolutionary adaptation, standing as a testament to the extraordinary diversity of survival strategies within the tree squirrel family. While Fox Squirrels and Eastern Gray Squirrels succeed through adaptability, and American Red Squirrels and Douglas Squirrels master territorial systems in their respective forest types, Abert’s Squirrels have achieved something entirely different – complete integration with a single tree species across some of the most challenging mountain environments in North America.

Their dramatic ear tufts, magnificent plume-like tails, and sophisticated ponderosa pine processing abilities represent millions of years of evolution toward perfect specialization. Unlike the Mexican Fox Squirrel that shares southwestern mountain ranges but utilizes diverse forest types, Abert’s Squirrels have committed their evolutionary fate entirely to ponderosa pine ecosystems.

This specialization creates both extraordinary success within their chosen habitat and profound vulnerability to environmental changes. Their dependence on mature ponderosa pine forests makes them living indicators of southwestern mountain ecosystem health, while their sensitivity to habitat alterations serves as an early warning system for broader environmental changes affecting entire forest communities.

The conservation challenges facing Abert’s Squirrels – climate change impacts on high-elevation forests, habitat fragmentation from development and infrastructure, and altered fire regimes affecting forest structure – represent broader threats to southwestern mountain ecosystems. Their conservation success requires landscape-scale thinking and long-term commitment to maintaining the integrity of ponderosa pine forest communities.

Understanding Abert’s Squirrel ecology reveals the intricate relationships between specialist species and their environments, demonstrating how evolutionary specialization can create both remarkable efficiency and conservation vulnerability. Their sophisticated bark processing techniques, mycorrhizal fungi relationships, and seasonal migration patterns showcase the complex adaptations possible when species commit fully to specific ecological niches.

Whether observing their graceful movements among towering ponderosa pines, marveling at their distinctive ear tufts silhouetted against mountain skies, or studying their sophisticated forest relationships, Abert’s Squirrels offer profound insights into the complexity and beauty of specialized evolutionary adaptations. Their presence indicates healthy, functioning ponderosa pine ecosystems and represents our connection to the unique natural heritage of southwestern mountain forests.

The future of Abert’s Squirrels depends on our commitment to preserving the mature ponderosa pine forests they require and managing these ecosystems to accommodate both human needs and wildlife conservation. Through sustainable forest management, habitat connectivity maintenance, and recognition of their unique ecological requirements, we can ensure that future generations will continue to experience these magnificent specialists in their mountain forest homes.

In a rapidly changing world where generalist species often dominate modified landscapes, Abert’s Squirrels remind us of the irreplaceable value of specialist species and the intact ecosystems that sustain them. Their conservation represents both a practical necessity for southwestern forest health and a symbolic commitment to preserving the remarkable diversity of life that characterizes North America’s mountain regions.