The morning fog lifts from the towering coastal redwoods as a sharp, piercing chatter cuts through the forest silence. High above, a small olive-brown blur spirals down a massive Douglas fir trunk with lightning speed, pausing momentarily to deliver a scolding tirade before vanishing into the emerald canopy. This feisty Pacific Coast native is the Douglas Squirrel – the American Red Squirrel’s equally spirited western cousin and the undisputed voice of the Pacific Northwest forests.

The Douglas Squirrel (Tamiasciurus douglasii) is the Pacific Coast’s specialist tree squirrel, distinguished by its olive-brown coloration, incredible agility, and mastery of towering coniferous forests from British Columbia to California. While sharing territorial intensity with the American Red Squirrel, Douglas Squirrels occupy entirely different ecosystems than the oak-preferring Western Gray Squirrel, the adaptable Fox Squirrel, the forest-generalist Eastern Gray Squirrel, or the specialized Abert’s Squirrel and Mexican Fox Squirrel found in southwestern regions.

| Attribute | Details |

|---|---|

| Scientific Name | Tamiasciurus douglasii |

| Size | 10-14 inches total length |

| Weight | 150-300 grams (0.3-0.7 lbs) |

| Lifespan | 4-9 years wild, up to 12 years maximum |

| Habitat | Pacific Coast coniferous forests, redwood groves |

| Diet | Specialist: conifer seeds, fungi, tree sap, nuts |

| Activity | Diurnal (most active dawn and dusk) |

| Conservation Status | Least Concern (stable populations) |

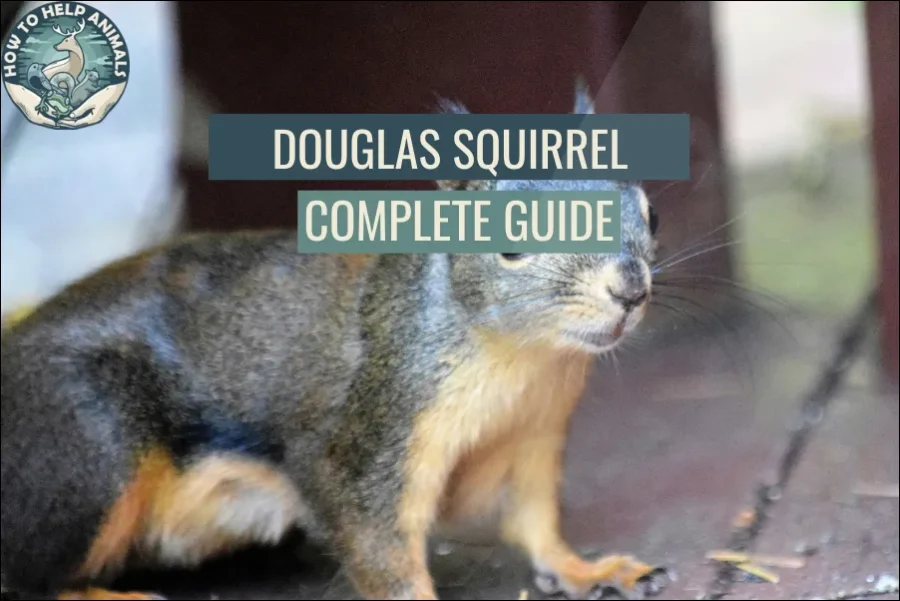

Physical Description & Identification

Size and Build Characteristics

Douglas Squirrels share the compact, energetic build of their close relative the American Red Squirrel, but display distinct differences that reflect their adaptation to Pacific Coast forest environments. Measuring 10-14 inches from nose to tail tip, they fall into the smaller category of North American tree squirrels, considerably smaller than the robust Fox Squirrel or the impressive Western Gray Squirrel that also inhabits western forests.

Their lightweight build (150-300 grams) provides significant advantages for navigating the extreme heights of coastal conifers, where they can access resources unavailable to larger species like Eastern Gray Squirrels. This size allows them to venture onto branches that would never support the weight of an Abert’s Squirrel or Mexican Fox Squirrel, giving them exclusive access to the choicest conifer cones at branch tips.

The Douglas Squirrel’s muscular, compact frame reflects evolutionary adaptations for life in some of North America’s most challenging arboreal environments, where agility and energy efficiency prove more valuable than the raw strength that benefits ground-foraging Fox Squirrels.

Distinctive Coloration and Seasonal Variations

Summer Coat (April-September): Douglas Squirrels display a distinctive olive-brown to grayish-brown dorsal coloration that sets them apart from the rust-red coat of American Red Squirrels. This more muted coloration provides excellent camouflage among the bark patterns of Douglas fir, Sitka spruce, and western hemlock – their primary habitat trees.

The underside shows a striking orange-yellow to bright rusty-orange belly that creates a sharp contrast with the darker back, similar to American Red Squirrels but typically more vibrant and extensive. This bright ventral coloration becomes particularly noticeable when Douglas Squirrels assume their characteristic alert postures.

Winter Coat (October-March): Winter pelage grows considerably denser and often displays more grayish tones, with the olive-brown summer coloration becoming more muted. Like American Red Squirrels, many Douglas Squirrels develop prominent ear tufts during winter months, though these are typically smaller and less dramatic than those of their eastern cousins.

Regional Variations: Across their Pacific Coast range, Douglas Squirrels show subtle but consistent geographic variations:

- Northern populations (British Columbia/Washington): Darker, more grayish coloration

- Central populations (Oregon): Classic olive-brown appearance

- Southern populations (California): Slightly lighter, more brownish tones

- Coastal populations: Often darker and more saturated colors

- Interior mountain populations: Lighter, more grayish coloration

Distinguishing Features from Related Species

Comparison with American Red Squirrels:

- Coloration: Olive-brown back vs. rust-red back

- Size: Slightly smaller average body size

- Habitat: Coastal conifers vs. boreal/montane forests

- Ear tufts: Smaller, less prominent winter tufts

- Tail: Often more brownish, less reddish coloration

Distinction from Larger Western Squirrels:

- Size difference: Dramatically smaller than Western Gray Squirrels or Fox Squirrels.

- Coloration: Olive-brown vs. silver-gray (Western Gray) or variable (Fox Squirrel)

- Behavior: Highly territorial vs. more tolerant social systems

- Habitat: Coniferous specialists vs. oak woodland preferences

- Vocalizations: More frequent and varied calling patterns

Behavioral Identification:

- Extreme agility: Remarkable speed and acrobatic ability in tall trees

- Vocal intensity: Constant chattering and territorial calling

- Territorial aggression: Fierce defense of resources and territory

- Cone cutting: Distinctive sound of cone harvesting activities

- Rapid movements: Quick, jerky locomotion contrasting with deliberate movements of larger squirrels

Physical Adaptations:

- Enhanced claws: Exceptionally sharp, curved claws for gripping massive tree trunks

- Flexible spine: Extraordinary spinal flexibility for navigating complex branch systems

- Large eyes: Proportionally large eyes adapted for forest environments

- Powerful hindquarters: Strong leg muscles enabling impressive leaping distances

- Specialized teeth: Adapted for processing tough conifer seeds and bark

Habitat & Distribution

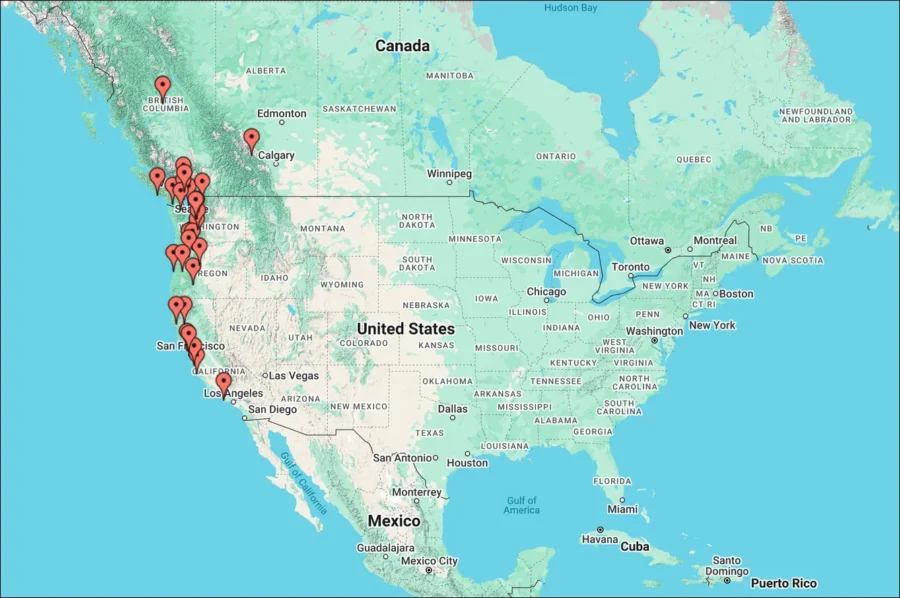

Pacific Coast Range and Biogeographic Distribution

Douglas Squirrels occupy a narrow but ecologically rich range along North America’s Pacific Coast, extending from British Columbia through Washington, Oregon, and into northern California. This distribution represents one of the most geographically restricted ranges among North American tree squirrels, contrasting sharply with the continent-spanning ranges of Fox Squirrels or Eastern Gray Squirrels.

Their range closely follows the distribution of Pacific Coast coniferous forests, particularly those dominated by Douglas fir, western hemlock, Sitka spruce, and coastal redwoods. Unlike the adaptable American Red Squirrel that occupies diverse northern forests, or the specialized Abert’s Squirrel restricted to southwestern ponderosa pine forests, Douglas Squirrels have evolved as masters of the unique coastal temperate rainforest ecosystem.

Geographic Range Boundaries:

- Northern limit: Coastal British Columbia and southern Alaska

- Southern limit: Northern California coastal and Sierra Nevada forests

- Eastern extent: Cascade Range and Sierra Nevada mountains

- Western boundary: Pacific Ocean coastal forests

- Elevational range: Sea level to approximately 8,000 feet

Coastal Temperate Rainforest Specialization

Primary Habitat Requirements: Douglas Squirrels demonstrate extreme specialization for coastal temperate rainforest environments that support some of the world’s tallest and most productive coniferous forests. These ecosystems differ dramatically from the oak woodlands preferred by Western Gray Squirrels or the mixed forests utilized by Eastern Gray Squirrels.

Optimal Forest Characteristics:

- Canopy dominance: Old-growth and mature second-growth coniferous forests

- Tree species: Douglas fir, western hemlock, Sitka spruce, western red cedar

- Vertical structure: Multi-layered canopies providing diverse microhabitats

- Moisture regime: High humidity and consistent precipitation

- Understory: Minimal ground vegetation allowing easy movement

- Snag availability: Dead trees providing cavity nesting opportunities

Conifer Species Associations:

- Douglas fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii): Primary habitat tree providing food and shelter

- Western hemlock (Tsuga heterophylla): Important for dense cover and cone resources

- Sitka spruce (Picea sitchensis): Crucial in coastal environments

- Western red cedar (Thuja plicata): Valuable for nest sites and territory boundaries

- Noble fir (Abies procera): Important at higher elevations

- Coast redwood (Sequoia sempervirens): Utilized in southern range portions

Redwood Forest Adaptations

Unique Redwood Ecosystem Requirements: In their southern range, Douglas Squirrels have adapted to life among coast redwoods – some of Earth’s tallest trees. These environments present unique challenges and opportunities unavailable to any other North American squirrel species, including the oak-specialist Abert’s Squirrel or the montane-adapted Mexican Fox Squirrel.

Redwood Forest Specializations:

- Extreme height navigation: Ability to forage at heights exceeding 200 feet

- Fog adaptation: Behavioral and physiological adaptations to coastal fog

- Canopy complexity: Navigation of intricate redwood crown structures

- Microclimate utilization: Exploitation of diverse temperature and humidity zones

- Epiphyte communities: Utilization of aerial garden ecosystems in redwood crowns

Elevation and Climate Zonation:

- Coastal fog zone (0-1,500 feet): Redwood and Sitka spruce dominance

- Montane zone (1,500-4,000 feet): Douglas fir and western hemlock forests

- Subalpine zone (4,000-8,000 feet): Noble fir and mountain hemlock forests

- Rain shadow areas: Drier forests with different species compositions

- Interior valleys: Mixed coniferous forests with reduced maritime influence

Territory Structure and Habitat Micromanagement

Territory Organization: Douglas Squirrels maintain territory systems similar to American Red Squirrels but adapted to the unique structure of Pacific Coast forests. Their territories differ significantly from the more extensive ranges typical of Fox Squirrels or the variable territories of Eastern Gray Squirrels.

Territory Characteristics:

- Size: 0.5-3.0 acres depending on forest productivity and tree density

- Vertical component: Three-dimensional territories extending from forest floor to canopy

- Midden locations: Strategic placement of food storage sites near water and shelter

- Nest tree selection: Multiple cavity options distributed throughout territory

- Boundary markers: Scent and vocal marking of territorial limits

Microhabitat Specialization:

- Canopy zones: Different activities concentrated at specific height levels

- Branch highways: Preferred travel routes through interconnected branches

- Feeding stations: Specific locations for cone processing activities

- Cache sites: Strategic food storage locations throughout vertical territory

- Resting areas: Sheltered spots for midday rest and weather protection

Resource Management Systems:

- Cone harvest zones: Areas designated for intensive seasonal collection

- Fungal territories: Specific areas managed for mushroom cultivation and harvest

- Sap collection sites: Trees maintained for seasonal sap extraction

- Water access: Territory boundaries ensuring reliable water source access

- Escape routes: Multiple pathways for predator avoidance and territorial defense

Diet & Feeding Behavior

Coniferous Forest Dietary Specialization

Douglas Squirrels have evolved feeding strategies specifically adapted to Pacific Coast coniferous forests, displaying even greater specialization than American Red Squirrels while occupying entirely different ecosystems than the oak-dependent Western Gray Squirrels or the more generalized Fox Squirrels and Eastern Gray Squirrels.

Seasonal Dietary Adaptations:

Spring Diet (March-May):

- Conifer shoots: Fresh growth from Douglas fir, hemlock, and spruce

- Tree sap extraction: Specialized bark gnawing accessing sugar-rich sap

- Cached conifer seeds: Stored supplies from previous autumn harvest

- Early fungi: Spring mushrooms including oyster mushrooms and polypores

- Bird eggs and nestlings: Supplemental protein during breeding season

- Lichen and moss: Moisture-rich vegetation during dry periods

Summer Diet (June-August):

- Developing cones: Immature cones harvested before seed release

- Diverse fungi: Peak mushroom season with chanterelles, boletes, and matsutake

- Tree flowers: Conifer pollen cones and occasional deciduous tree blossoms

- Insects and larvae: Protein sources including bark beetles and caterpillars

- Fresh vegetation: Limited consumption of herbs and leafy materials

- Berries: Seasonal fruits from understory shrubs like huckleberry and salmonberry

Autumn Diet (September-November):

- Primary focus: Intensive conifer cone harvesting and processing

- Douglas fir cones: Preferred food source with high-quality seeds

- Hemlock and spruce cones: Secondary cone sources providing dietary variety

- Hazelnuts and acorns: Occasional supplement when available in mixed forests

- Late-season fungi: Autumn mushroom species extending fungal foraging

- Increased caloric intake: Energy storage for winter survival periods

Winter Diet (December-February):

- Cached seed reliance: Primary dependence on stored conifer seeds

- Inner bark consumption: Cambium layer accessing during scarcity periods

- Remaining cone supplies: Systematic use of stored cone resources

- Limited fresh food: Reduced availability of fresh vegetation

- Opportunistic feeding: Available lichens, mosses, and persistent fungi

- Energy conservation: Reduced activity minimizing caloric requirements

Cone Harvesting and Processing Mastery

Douglas Squirrels have perfected cone harvesting techniques specifically adapted to Pacific Coast conifers, displaying processing behaviors that surpass even the sophisticated techniques of American Red Squirrels while handling entirely different cone types than those processed by Abert’s Squirrels in southwestern pine forests.

Specialized Harvesting Techniques:

- Green cone cutting: Harvesting before cones open prevents seed loss

- Species-specific timing: Different harvest schedules for various conifer species

- Height-based collection: Access to cones at extreme heights unavailable to larger squirrels

- Weather timing: Harvest scheduling based on Pacific Coast weather patterns

- Quality selection: Ability to assess cone quality and seed content before cutting

Advanced Processing Methods:

- Sequential scale removal: Systematic stripping technique maximizing seed extraction

- Seed quality assessment: Rapid evaluation and sorting of individual seeds

- Waste minimization: Efficient processing reducing energy expenditure

- Tool utilization: Use of specialized gnawing techniques and positions

- Speed optimization: Rapid processing enabling maximum daily harvest volumes

Fungal Cultivation and Harvesting

Perhaps more than any other North American squirrel species, Douglas Squirrels have developed sophisticated relationships with forest fungi that approach agricultural management, representing behaviors completely different from the nut-focused caching of Fox Squirrels or Eastern Gray Squirrels.

Fungal Management Strategies:

- Habitat cultivation: Creating optimal conditions for mushroom growth

- Spore dispersal: Intentional distribution of fungal spores throughout territory

- Harvest timing: Precise timing of mushroom collection for optimal nutrition

- Drying techniques: Preparation of fungi for long-term storage

- Species selection: Preference for specific mushroom species based on nutritional value

Mushroom Processing and Storage:

- Fresh consumption: Immediate eating of highest-quality specimens

- Drying preparation: Systematic preparation of fungi for preservation

- Cache integration: Incorporation of dried mushrooms into food storage systems

- Seasonal rotation: Strategic use of fungal resources throughout the year

- Quality maintenance: Inspection and maintenance of stored fungal supplies

Ecological Relationships:

- Mycorrhizal partnerships: Indirect support of tree-fungal relationships

- Spore dispersal services: Unintentional but beneficial fungal reproduction assistance

- Forest health contributions: Fungal management supporting ecosystem functions

- Nutrient cycling: Participation in forest nutrient distribution systems

- Biodiversity support: Fungal harvesting practices supporting forest diversity

Midden Systems and Food Storage

Douglas Squirrels employ midden systems similar to American Red Squirrels but adapted to Pacific Coast forest conditions and the unique challenges of coastal temperate rainforest environments, creating storage systems far more sophisticated than the scatter-caching typical of Fox Squirrels or Western Gray Squirrels.

Pacific Coast Midden Adaptations:

- Moisture management: Specialized techniques preventing mold and decay in humid environments

- Drainage considerations: Strategic placement ensuring proper water drainage

- Size optimization: Midden dimensions adapted to local cone and seed types

- Location selection: Positioning considering coastal weather patterns and forest structure

- Multi-species storage: Accommodation of diverse Pacific Coast conifer seeds

Cache Organization and Maintenance:

- Layered storage systems: Organized placement preventing spoilage and maximizing access

- Inventory rotation: Systematic use preventing waste and spoilage

- Expansion planning: Gradual midden enlargement based on territory productivity

- Pest management: Behavioral strategies reducing insect and rodent intrusion

- Weather protection: Techniques protecting caches from Pacific Coast storms

Long-term Storage Strategies:

- Multi-year accumulation: Building food supplies spanning multiple seasons

- Emergency reserves: Maintenance of backup caches for catastrophic loss protection

- Quality control: Regular inspection and maintenance of stored materials

- Access planning: Strategic cache placement ensuring winter accessibility

- Theft prevention: Defensive behaviors protecting valuable food stores

Reproduction & Life Cycle

Breeding Season and Pacific Coast Adaptations

Douglas Squirrels typically experience a single annual breeding season, with timing closely synchronized to Pacific Coast climate patterns and the unique seasonal rhythms of coastal temperate rainforests. Their reproductive strategy shows distinct adaptations compared to the more variable breeding patterns of Fox Squirrels, Eastern Gray Squirrels, or the different environmental pressures facing American Red Squirrels in boreal forests.

Primary Breeding Season (February-April): Douglas Squirrel breeding occurs during late winter and early spring, synchronized with the coastal Pacific’s mild winter temperatures and early spring growth. This timing differs from both the harsh winter breeding of American Red Squirrels and the more flexible seasonal patterns of adaptable species like Fox Squirrels.

Pacific Coast Environmental Influences:

- Mild winter conditions: Coastal moderation allowing earlier breeding than interior species

- Fog season timing: Breeding synchronized with optimal humidity conditions

- Food resource availability: Breeding timing ensuring offspring development during resource abundance

- Daylight patterns: Photoperiod triggers modified by maritime climate influences

- Storm season avoidance: Reproductive timing avoiding peak Pacific storm periods

Geographic Breeding Variations:

- Northern populations (British Columbia/Washington): Later breeding due to cooler conditions

- Central populations (Oregon): Peak breeding season timing

- Southern populations (California): Earlier breeding in warmer coastal zones

- Elevation influences: Mountain populations showing delayed breeding

- Coastal vs. interior: Maritime populations breeding earlier than inland territories

Courtship Behaviors in Tall Forest Environments

Douglas Squirrel courtship involves spectacular aerial displays and intense vocal competitions adapted to the unique challenges of Pacific Coast giant tree environments, creating courtship behaviors distinct from those of American Red Squirrels while displaying territorial intensity unknown among larger, more social species like Eastern Gray Squirrels.

Pre-Mating Behaviors:

- Canopy chasing: Extended high-speed pursuits through towering tree crowns

- Territorial expansion: Temporary enlargement of territories accessing potential mates

- Vocal competitions: Intense calling contests between competing males

- Scent marking intensification: Enhanced chemical communication throughout vertical territories

- Acrobatic displays: Spectacular jumping and climbing demonstrations

Mating Process: Female Douglas Squirrels mate with multiple males during their 6-8 hour receptive period, similar to American Red Squirrels but adapted to the three-dimensional territory structure of Pacific Coast forests.

Courtship Communication:

- Long-distance calling: Vocalizations adapted to penetrate dense forest canopies

- Visual displays: Tail flagging and body positioning visible through forest layers

- Scent trail marking: Chemical communication spanning vertical territory dimensions

- Physical demonstrations: Agility displays showcasing male fitness and territory quality

- Territory tours: Guided exploration of territory resources and quality

Nest Construction in Giant Tree Environments

Gestation Period: 32-36 days

Nest Site Selection: Douglas Squirrels face unique challenges in selecting nest sites among some of the world’s tallest trees, requiring adaptations beyond those needed by American Red Squirrels in smaller boreal trees or the cavity requirements of species like Abert’s Squirrels.

Giant Tree Cavity Utilization:

- Redwood cavities: Natural hollows in ancient redwood giants

- Douglas fir hollows: Cavities in mature Pacific Coast conifers

- Woodpecker excavations: Modified holes in large-diameter trees

- Storm damage sites: Cavities created by wind and weather damage

- Bark pocket formations: Natural formations in thick-barked species

Extreme Height Nest Construction:

- High-elevation dreys: External nests built at extraordinary heights

- Wind resistance: Construction techniques adapted to coastal storm conditions

- Moisture protection: Building methods preventing rain and fog penetration

- Multi-level design: Nest structures adapted to complex branch arrangements

- Emergency accessibility: Multiple entrance/exit routes essential at extreme heights

Construction Materials and Techniques:

- Regional materials: Pacific Coast-specific materials including redwood bark and cedar strips

- Weather resistance: Materials selection for coastal climate durability

- Insulation optimization: Thermal regulation in humid coastal environments

- Structural integrity: Engineering for coastal wind and storm conditions

- Camouflage integration: Concealment among Pacific Coast forest textures

Offspring Development in Pacific Environments

Birth Characteristics: Douglas Squirrel litters typically contain 2-4 young, born after the 32-36 day gestation period, with development patterns adapted to Pacific Coast seasonal cycles.

Newborn Features:

- Size: Approximately 2.8 inches long, weighing 10-14 grams

- Appearance: Pink, hairless, with closed eyes and ears

- Development: Moderate maturation rate balancing size constraints with environmental demands

Developmental Timeline:

Weeks 1-2:

- Rapid growth: Doubling birth weight through nutrient-rich maternal milk

- Thermoregulation: Complete dependence on mother in humid coastal climate

- First olive-brown fur: Beginning of distinctive Pacific Coast coloration

Weeks 3-4:

- Eye opening: Eyes open around day 20-24

- Hearing development: Ear function beginning around day 22-26

- Motor coordination: Initial balance and movement development

- Nest exploration: Short ventures within cavity or drey structure

Weeks 5-6:

- First emergence: Initial exploration outside nest in towering tree environment

- Solid food introduction: Beginning consumption of processed conifer seeds

- Vocal development: Species-specific calls adapted to forest penetration

- Climbing instruction: Maternal teaching of vertical navigation skills

Weeks 7-8:

- Weaning transition: Gradual reduction of nursing dependency

- Foraging education: Learning Pacific Coast-specific food processing techniques

- Territory exploration: Guided tours of three-dimensional territory structure

- Predator awareness: Education about aerial and arboreal threats

Weeks 9-11:

- Independence preparation: Extended time away from maternal supervision

- Skill mastery: Advanced cone processing and fungal identification

- Territorial boundaries: Understanding of Pacific Coast forest territory systems

- Dispersal readiness: Preparation for establishing individual territories

Extended Maternal Investment: Douglas Squirrel mothers provide intensive education in the complex skills required for surviving in Pacific Coast giant tree environments, including navigation techniques, cone processing methods, and midden management strategies unique to coastal temperate rainforest ecosystems.

Behavior & Social Structure

Territorial Intensity in Vertical Forest Environments

Douglas Squirrels maintain territorial systems that rival American Red Squirrels in intensity while adapting to the unique three-dimensional challenges of Pacific Coast giant tree environments. Their territorial behavior differs markedly from the more flexible social systems of Fox Squirrels, Eastern Gray Squirrels, or Western Gray Squirrels.

Three-Dimensional Territory Management:

- Vertical zonation: Different territory functions at various canopy heights

- Canopy highways: Preferred travel routes through interconnected branches

- Multi-level defense: Territorial protection spanning forest floor to crown

- Height-based resources: Exclusive access to canopy-specific food sources

- Escape route maintenance: Multiple pathways for three-dimensional predator avoidance

Territory Defense Adaptations:

- Long-distance surveillance: Visual monitoring across expansive forest views

- Acoustic territoriality: Vocalizations adapted to penetrate dense canopies

- Scent marking systems: Chemical communication spanning vertical territory dimensions

- Physical confrontation: Aggressive interactions adapted to extreme heights

- Resource protection: Intensive defense of cone sources and midden sites

Boundary Establishment and Maintenance:

- Natural landmarks: Territory boundaries following ridge lines and drainage patterns

- Tree-based markers: Scent marking on prominent forest giants

- Vocal advertising: Regular calling from elevated perches

- Patrol routes: Systematic inspection of three-dimensional territory boundaries

- Neighbor recognition: Stable relationships with adjacent territory holders

Communication in Giant Tree Environments

Douglas Squirrels have evolved communication systems specifically adapted to the acoustic challenges of dense Pacific Coast forests, developing vocalizations that differ from those of American Red Squirrels while maintaining similar territorial intensity.

Vocal Communication Adaptations:

Forest-Penetrating Calls:

- Rattle sequences: Rapid-fire calls adapted to cut through dense canopy layers

- Bark calls: Sharp, penetrating warnings for ground and aerial threats

- Whistle calls: Long-distance communication spanning forest valleys

- Chatter calls: Complex territorial advertisements reaching distant boundaries

Height-Specific Vocalizations:

- Canopy calls: High-frequency sounds optimized for treetop communication

- Mid-story calls: Intermediate-frequency vocalizations for branch-level interaction

- Ground calls: Lower-frequency sounds for forest floor communication

- Echo utilization: Vocal techniques using forest acoustics for amplification

Contextual Communication Systems:

- Threat assessment: Vocal variations indicating specific predator types and locations

- Social recognition: Individual vocal signatures allowing neighbor identification

- Reproductive calling: Specialized vocalizations during breeding season

- Territory quality: Vocal displays advertising territory resources and male fitness

Visual and Chemical Communication:

Long-Distance Visual Signaling:

- Tail flagging: Dramatic movements visible across forest clearings

- Body positioning: Postures communicating dominance and intent

- Movement patterns: Locomotion styles conveying emotional states and intentions

- Perch selection: Strategic positioning for maximum visual impact

Chemical Communication Networks:

- Scent highways: Chemical marking along major travel routes

- Territorial boundaries: Intensive scent marking at territory edges

- Resource marking: Chemical signals indicating food source ownership

- Individual identification: Unique scent signatures facilitating recognition

Daily Activity Patterns in Pacific Climate

Douglas Squirrels have adapted their daily routines to Pacific Coast climate patterns, particularly the influence of coastal fog, maritime temperatures, and the unique light conditions created by giant tree canopies.

Typical Daily Schedule:

Dawn Activity (Sunrise + 30 minutes to Mid-Morning):

- Fog navigation: Activity patterns adapted to coastal fog conditions

- Territory inspection: Systematic patrol optimizing limited visibility periods

- Peak foraging: Intensive food gathering during optimal temperature conditions

- Vocal advertising: Morning territorial calling cutting through forest silence

Midday Behavior (Late Morning to Early Afternoon):

- Canopy rest: Energy conservation in elevated, shaded locations

- Grooming activities: Coat maintenance in humid coastal environment

- Cache management: Organization of food storage during quiet periods

- Predator avoidance: Reduced activity during peak raptor hunting hours

Evening Activity (Late Afternoon to Sunset):

- Final foraging: Last intensive feeding before overnight rest

- Midden maintenance: End-of-day organization of food storage sites

- Social interactions: Brief encounters with neighboring territory holders

- Nest preparation: Evening shelter preparation adapted to coastal weather

Seasonal Activity Modifications:

- Fog season (Summer): Activity patterns synchronized with fog cycles

- Storm season (Winter): Reduced activity during Pacific Coast storm periods

- Breeding season (Spring): Extended dawn activity during courtship and mating

- Cone harvest season (Autumn): Maximum activity driven by intensive collection

Social Relationships and Competitive Dynamics

Despite maintaining intense territorial systems similar to American Red Squirrels, Douglas Squirrels have developed social adaptations specific to Pacific Coast forest environments and the challenges of living among the world’s tallest trees.

Neighbor Recognition Systems:

- Stable boundaries: Long-term territorial relationships between established residents

- Familiar neighbor tolerance: Reduced aggression toward recognized adjacent territory holders

- Information networks: Indirect communication about forest conditions and threats

- Cooperative predator detection: Shared vigilance systems spanning multiple territories

- Resource respect: Recognition of neighbor territory rights during resource abundance

Competitive Interaction Management:

- Height-based competition: Territorial disputes adapted to three-dimensional forest structure

- Resource competition: Intensive competition for cone sources and prime cavity sites

- Temporal partitioning: Staggered activity patterns reducing direct competitive encounters

- Stress reduction: Behavioral adaptations managing high-density population stress

- Conflict resolution: Behavioral patterns minimizing energy-costly territorial disputes

Social Learning Networks:

- Foraging technique transmission: Learning optimal cone processing methods from neighbors

- Predator information sharing: Communication about threat locations and behavior patterns

- Environmental assessment: Social learning about territory quality and resource availability

- Adaptation strategies: Collective responses to environmental changes and challenges

- Cultural transmission: Behavioral traditions passed between generations and neighbors

Interaction with Humans and Conservation

Pacific Northwest Urban Adaptation

Douglas Squirrels show moderate success in urban and suburban environments that maintain adequate Pacific Coast coniferous habitat, though their urban adaptability remains more limited than that achieved by Fox Squirrels, Eastern Gray Squirrels, or even American Red Squirrels in suitable northern cities.

Urban Habitat Requirements:

- Mature Pacific Coast conifers: Parks and neighborhoods with Douglas fir, hemlock, or spruce

- Adequate territory size: Sufficient space for maintaining territorial systems

- Cone production capability: Urban trees capable of producing adequate food resources

- Nesting opportunities: Cavities or suitable sites for drey construction

- Reduced disturbance: Areas with limited high-intensity human activity

Urban Behavioral Adaptations:

- Modified territorial size: Smaller territories in high-quality urban coniferous habitat

- Noise tolerance: Adaptation to urban sound environments while maintaining vocal communication

- Human proximity tolerance: Increased acceptance of human presence within territories

- Activity pattern shifts: Adjustment to human activity schedules and urban lighting

- Alternative food utilization: Limited use of urban food sources supplementing natural diet

Urban Population Characteristics:

- Density variations: Higher densities possible in optimal urban coniferous environments

- Behavioral modifications: Reduced territorial aggression in stable urban environments

- Health considerations: Urban stress factors and pollution impacts on population health

- Genetic effects: Potential impacts of habitat fragmentation on genetic diversity

- Human interaction patterns: Development of urban-specific behavioral responses

Human-Wildlife Conflict and Management Strategies

Human-Wildlife Conflict and Management Strategies

Douglas Squirrels create specific types of conflicts different from those typical of larger squirrel species, primarily related to their intense vocalizations and territorial behaviors rather than the property damage more common with Fox Squirrels or building invasion issues seen with Eastern Gray Squirrels.

Common Pacific Northwest Conflicts:

- Noise disturbances: Loud territorial calling disturbing residents, especially during dawn hours

- Building occupation: Nesting in attics and structures with suitable cavity access

- Garden interactions: Limited damage through territorial activities and occasional plant consumption

- Bird feeder competition: Aggressive exclusion of birds from feeding stations

- Aggressive territorial defense: Perceived threats to humans and pets during breeding season

Regional Conflict Resolution Approaches:

Noise Management in Pacific Communities:

- Habitat modification: Reducing attractive territorial features near residential areas

- Tree management: Strategic pruning redirecting territorial boundaries away from homes

- Community education: Public awareness about natural behavioral patterns and seasonal intensity

- Timing understanding: Education about peak vocal activity periods and breeding season behaviors

Structural Protection Methods:

- Entry point sealing: Securing openings smaller than 1.5 inches to prevent building access

- Branch management: Trimming overhanging branches reducing structural access routes

- Barrier installation: Physical deterrents adapted to Pacific Coast architectural styles

- Alternative nesting: Providing species-appropriate nest boxes away from conflict areas

Pacific Northwest Coexistence Strategies:

- Native habitat enhancement: Creating suitable Douglas Squirrel habitat away from sensitive areas

- Regional education programs: Community outreach about Pacific Coast squirrel ecology

- Professional consultation: Wildlife specialists familiar with regional Douglas Squirrel behavior

- Municipal planning: Urban forestry practices supporting appropriate squirrel habitat distribution

Feeding Guidelines for Pacific Coast Residents

Appropriate Supplemental Feeding: Douglas Squirrels benefit from careful supplemental feeding using foods native to Pacific Coast ecosystems, though their specialized requirements differ significantly from the more generalized diets acceptable to Fox Squirrels or Eastern Gray Squirrels.

Recommended Regional Foods:

- Native Pacific conifer seeds: Douglas fir seeds, hemlock seeds when locally available

- Regional nuts: Hazelnuts native to Pacific Coast ecosystems

- Pacific fungi: Commercially available mushroom species safe for wildlife consumption

- Raw, unsalted nuts: Walnuts and almonds in very limited quantities

Foods to Avoid:

- Non-native seeds: Bird seed mixes inappropriate for specialized Pacific Coast diet

- Processed human foods: Bread, crackers, cookies completely unsuitable for Douglas Squirrels

- Salted or flavored items: Causing dehydration and health complications

- Chocolate products: Containing compounds toxic to small mammals

- Inappropriate nuts: Species not native to Pacific Coast ecosystems

Pacific Coast Feeding Best Practices:

- Minimal intervention: Feeding should minimally supplement excellent natural food sources

- Seasonal awareness: Increased feeding only during harsh Pacific storm periods

- Location selection: Feeding areas positioned away from roads and urban hazards

- Cleanliness protocols: Regular cleaning preventing disease transmission and pest attraction

- Native ecosystem support: Feeding practices supporting rather than disrupting natural foraging

Educational and Research Opportunities in Pacific Forests

Douglas Squirrels provide unique opportunities for studying territorial behavior, vocal communication, and Pacific Coast forest ecology unavailable with other North American squirrel species including American Red Squirrels, Abert’s Squirrels, or Mexican Fox Squirrels.

Optimal Research and Observation Conditions:

- Early morning hours (5:30-8:30 AM): Peak territorial activity and vocal behavior

- Late afternoon periods (4-7 PM): Active foraging and territorial maintenance

- Autumn months (August-October): Intensive cone harvesting and caching behavior

- Breeding season (February-April): Courtship displays and territorial competition

Unique Behavioral Study Opportunities:

- Three-dimensional territoriality: Study of vertical territory management in giant tree environments

- Pacific Coast vocal adaptations: Documentation of forest-penetrating communication systems

- Fungal relationship studies: Investigation of sophisticated mushroom cultivation and management

- Giant tree navigation: Analysis of locomotion and navigation in extreme-height environments

Educational Value for Pacific Coast Conservation:

- Old-growth forest dependencies: Demonstration of species requiring mature forest ecosystems

- Territorial system complexity: Examples of sophisticated animal space use and resource management

- Pacific Coast specialization: Understanding of regional ecosystem adaptations and requirements

- Conservation indicator species: Douglas Squirrels as indicators of healthy Pacific Coast forest ecosystems

Citizen Science and Community Involvement:

- Pacific Coast population monitoring: Contributing to regional Douglas Squirrel distribution surveys

- Behavioral documentation: Recording observations specific to Pacific Coast environments

- Forest health assessment: Using Douglas Squirrel presence as forest ecosystem quality indicator

- Climate change research: Documenting responses to changing Pacific Coast climate conditions

Conservation Status and Regional Management

Population Assessment and Pacific Coast Trends

Douglas Squirrels currently maintain stable populations across most of their Pacific Coast range, though their conservation status requires ongoing monitoring due to their restricted geographic distribution and dependence on mature coniferous forest ecosystems unlike the broader habitat tolerances of Fox Squirrels, Eastern Gray Squirrels, or American Red Squirrels.

Range-Wide Population Status:

- Overall trend: Stable across core Pacific Coast habitats

- Old-growth dependencies: Populations closely tied to mature forest preservation

- Urban populations: Limited but stable in suitable coniferous urban environments

- Climate sensitivity: Populations vulnerable to Pacific Coast climate change impacts

- Habitat fragmentation effects: Localized declines in highly fragmented landscapes

Regional Population Variations:

- British Columbia: Strong populations in protected coastal temperate rainforests

- Washington State: Healthy populations with some pressure from urban development

- Oregon: Generally stable with habitat management concerns in some areas

- Northern California: Stable populations facing increasing development pressure

- Redwood ecosystems: Specialized populations dependent on ancient forest preservation

Threats Specific to Pacific Coast Ecosystems

Climate Change Impacts on Coastal Forests: Douglas Squirrels face unique climate challenges specific to Pacific Coast ecosystems, including changes in fog patterns, precipitation timing, and temperature regimes that differ from climate pressures facing American Red Squirrels in boreal forests or Abert’s Squirrels in southwestern mountains.

Pacific Coast Climate Concerns:

- Fog pattern changes: Alterations in coastal fog affecting forest moisture regimes

- Precipitation shifts: Changes in Pacific storm patterns impacting forest productivity

- Temperature increases: Warming affecting high-elevation and coastal forest composition

- Extreme weather events: Increased storm intensity damaging forest structure

- Ocean condition changes: Marine influences affecting coastal forest ecosystems

Old-Growth Forest Dependencies:

- Logging pressures: Continued harvesting of mature Pacific Coast forests

- Development conversion: Urban and suburban expansion into forest habitats

- Fire management impacts: Altered fire regimes affecting forest succession

- Fragmentation effects: Isolation of forest patches reducing population connectivity

- Second-growth limitations: Younger forests providing suboptimal habitat conditions

Specific Pacific Coast Threats:

- Coastal development: Residential and commercial development in critical habitats

- Recreation impacts: Hiking, camping, and recreational activities disturbing populations

- Air quality degradation: Pollution affecting forest health and squirrel populations

- Invasive species: Non-native plants and animals altering forest ecosystems

- Infrastructure development: Roads and utilities fragmenting forest habitats

Conservation Efforts and Pacific Regional Strategies

Old-Growth Forest Protection:

- Protected area expansion: Increasing acreage of preserved mature Pacific Coast forests

- Conservation easements: Private land protection maintaining Douglas Squirrel habitat

- Sustainable forestry practices: Logging methods preserving habitat connectivity and structure

- Restoration projects: Replanting and restoration of degraded Pacific Coast forest areas

Regional Research and Monitoring:

- Population surveys: Regular monitoring of Douglas Squirrel density and distribution

- Habitat quality assessment: Evaluation of forest conditions supporting sustainable populations

- Climate change research: Studies of Pacific Coast climate impacts on populations

- Behavioral ecology studies: Understanding habitat requirements and adaptation strategies

Pacific Coast Forest Management:

- Ecosystem-based management: Forest practices considering Douglas Squirrel habitat needs

- Connectivity planning: Maintaining forest corridors linking fragmented habitats

- Multi-species conservation: Integrated approaches benefiting entire Pacific Coast forest communities

- Adaptive management: Flexible strategies responding to changing environmental conditions

How to Help Douglas Squirrels

Creating Pacific Coast Squirrel Habitat

Property owners within Douglas Squirrel range can take specific actions supporting populations while recognizing that habitat requirements differ significantly from those needed by Eastern Gray Squirrels, Fox Squirrels, or even American Red Squirrels in different forest types.

Native Pacific Coast Tree Selection:

Primary Conifer Species:

- Douglas fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii): Essential primary habitat tree

- Western hemlock (Tsuga heterophylla): Important for dense cover and food production

- Sitka spruce (Picea sitchensis): Critical for coastal environments

- Western red cedar (Thuja plicata): Valuable for nesting sites and territory structure

- Noble fir (Abies procera): Beneficial for higher elevation properties

- Coast redwood (Sequoia sempervirens): Appropriate for suitable climate zones

Pacific Coast Landscape Management:

- Vertical habitat structure: Maintain diverse canopy layers supporting three-dimensional territories

- Mature tree preservation: Protect existing cone-producing age classes

- Natural cavity retention: Preserve trees with hollows when safely possible

- Native understory management: Support Pacific Coast native plant communities

- Water feature integration: Ensure reliable water access within potential territories

Regional Habitat Enhancement:

- Fog adaptation: Landscape design accommodating coastal fog patterns

- Storm resistance: Tree management considering Pacific Coast wind patterns

- Microclimate creation: Developing diverse temperature and humidity zones

- Canopy connectivity: Maintaining travel corridors between tree groups

- Seasonal resource availability: Ensuring year-round food and shelter resources

Property Management for Pacific Coast Conservation

Chemical-Free Forest Stewardship:

- Pesticide elimination: Avoid chemicals affecting Pacific Coast forest food webs

- Organic soil management: Use natural amendments supporting native tree health

- Integrated ecosystem management: Biological approaches supporting forest community health

- Native species emphasis: Focus on plants supporting Pacific Coast forest ecosystems

Nest Site and Territory Enhancement:

- Cavity tree preservation: Protect trees with existing natural hollows

- Snag management: Maintain dead trees when safely possible for nesting opportunities

- Specialized nest box installation: Boxes designed specifically for Douglas Squirrel requirements

- Territory structure support: Maintain habitat features supporting territorial systems

Seasonal Management Adaptations:

- Storm season preparation: Maintain protective forest structure for Pacific Coast weather

- Breeding season considerations: Minimize disturbance during February-April reproductive period

- Cone development protection: Avoid activities disrupting summer cone formation

- Autumn harvest respect: Reduce disturbance during intensive caching periods

Supporting Pacific Coast Squirrel Research

Regional Citizen Science Opportunities:

- Pacific Coast population monitoring: Participate in Douglas Squirrel distribution surveys

- Behavioral documentation: Record observations specific to Pacific Coast forest environments

- Climate change research: Document responses to changing Pacific Coast conditions

- Forest health assessment: Use Douglas Squirrel presence as ecosystem quality indicator

Research Support and Collaboration:

- Pacific Coast university partnerships: Support research on regional forest ecology

- Conservation organization funding: Contribute to organizations working on Pacific Coast conservation

- Private land research access: Allow scientists to conduct studies on suitable properties

- Community science participation: Engage in collaborative monitoring and research efforts

Educational Outreach and Advocacy:

- Pacific Coast conservation education: Share knowledge about regional forest ecosystem needs

- School program support: Environmental education focusing on Pacific Coast forest communities

- Responsible wildlife observation: Document Douglas Squirrel behaviors for educational purposes

- Conservation policy advocacy: Support protection of Pacific Coast old-growth forests

Forest Landowner Recommendations

Sustainable Pacific Coast Forestry:

- Selective harvest methods: Timber practices maintaining Douglas Squirrel habitat structure

- Retention forestry approaches: Leaving critical trees and habitat features during operations

- Rotation planning: Long-term forest management supporting continuous habitat availability

- Ecosystem service recognition: Understanding Douglas Squirrel contributions to forest health

Regional Conservation Programs:

- Pacific Coast conservation easements: Financial incentives for habitat protection

- Sustainable forestry certification: Programs rewarding wildlife-friendly forest management

- Regional cost-sharing programs: Government assistance for habitat enhancement projects

- Tax incentive utilization: Benefits for maintaining critical Pacific Coast forest habitats

Conclusion

The Douglas Squirrel represents one of North America’s most remarkable examples of regional specialization and evolutionary adaptation to unique Pacific Coast forest ecosystems. While sharing behavioral intensity with the American Red Squirrel and displaying territorial systems unknown among larger species like Fox Squirrels, Eastern Gray Squirrels, or Western Gray Squirrels, Douglas Squirrels have carved out an entirely distinct ecological niche among the giants of coastal temperate rainforests.

Their mastery of three-dimensional territories in some of Earth’s tallest trees, sophisticated fungal cultivation practices, and vocal communication systems adapted to dense forest environments demonstrate the extraordinary diversity of adaptive strategies within North American tree squirrel communities. Unlike the broad adaptability of Fox Squirrels or Eastern Gray Squirrels, Douglas Squirrels exemplify the remarkable success possible through extreme specialization.

Understanding Douglas Squirrel ecology reveals the intricate relationships between species evolution and ecosystem structure unique to Pacific Coast forests. Their dependence on old-growth and mature second-growth forests makes them excellent indicators of ecosystem health while highlighting the conservation challenges facing Pacific Coast biodiversity in an era of rapid environmental change.

The conservation of Douglas Squirrel populations benefits entire Pacific Coast forest communities, as their habitat requirements overlap extensively with countless other species dependent on mature coniferous forest ecosystems. Unlike the adaptable American Red Squirrels that can utilize various northern forests, or the specialized but geographically broader Abert’s Squirrels and Mexican Fox Squirrels, Douglas Squirrels require the preservation of specific Pacific Coast forest types.

Through sustainable forest management, old-growth forest protection, and recognition of their unique ecological requirements, we can ensure that future generations will continue to experience the remarkable energy and ecological importance of these Pacific Coast forest specialists. Their territorial calling echoing through coastal redwood groves and Douglas fir forests serves as a living reminder of the irreplaceable natural heritage of western North America.

Whether observing their spectacular acrobatic abilities among towering trees, listening to their complex forest-penetrating vocalizations, or studying their sophisticated territorial and food storage systems, Douglas Squirrels offer unparalleled opportunities for understanding specialized animal-environment relationships. Their presence indicates healthy, functioning Pacific Coast forest ecosystems and represents our connection to one of the world’s most remarkable temperate forest regions.

The Douglas Squirrel’s continued success depends on our commitment to preserving the old-growth and mature forest ecosystems they require. In a world where habitat generalists often dominate modified landscapes, Douglas Squirrels remind us of the irreplaceable value of specialized species and the intact natural ecosystems that sustain them. Their conservation represents both a practical necessity for Pacific Coast forest health and a symbolic commitment to preserving the wild character that defines the magnificent forests of America’s western coast.