A flash of movement catches your eye across the alpine meadow—a tiny striped figure scrambles up a weathered pine, cheeks bulging with seeds. At 8,000 feet elevation, where most small mammals struggle to survive, the Least Chipmunk thrives as North America’s smallest and most widespread chipmunk species.

The Least Chipmunk (Neotamias minimus) is North America’s smallest chipmunk species, weighing just 1-2 ounces and measuring 6-9 inches total length. Distinguished by prominent facial stripes extending to the ears and a grizzled gray-brown coat, they inhabit diverse ecosystems from sagebrush deserts to alpine forests across western North America.

| Attribute | Details |

|---|---|

| Scientific Name | Neotamias minimus |

| Size | 6-9 inches total length (3.5-4.5 inches body) |

| Weight | 28-56 grams (1-2 oz) |

| Lifespan | 2-5 years wild, up to 7 years maximum |

| Habitat | Coniferous forests, sagebrush, alpine meadows, 3,000-12,000 feet |

| Diet | Omnivore: conifer seeds, berries, fungi, insects, green vegetation |

| Activity | Diurnal (most active early morning and late afternoon) |

| Conservation Status | Least Concern (stable populations) |

Physical Description

The Least Chipmunk’s diminutive size immediately distinguishes it from other North American chipmunk species, including the larger Eastern Chipmunk found in deciduous forests. Their compact build reflects adaptations for life in harsh mountain environments where energy conservation proves critical for survival.

Five distinct dark stripes alternate with four lighter stripes running from nose to rump, creating the classic chipmunk pattern. However, their facial striping extends prominently to the ears—a key identification feature that separates them from other western chipmunk species. The central dark stripe runs along the spine, while lateral stripes follow the sides of the body.

Coat coloration varies significantly across their range, reflecting local environmental conditions and genetic variations. Northern populations typically display grizzled gray-brown dorsal fur with buff or white ventral coloring. Desert populations often show paler, more yellowish tones that provide camouflage against sandy soils and weathered rock.

Their tail accounts for roughly half their total body length and lacks the prominent bushiness seen in tree squirrels like the Northern Flying Squirrel. Instead, the tail appears flattened with alternating dark and light bands that continue the striped pattern. The underside typically shows orange-brown or rust coloration.

Seasonal coat changes help them adapt to extreme temperature variations in their mountain habitats. Summer pelage appears shorter and more vibrant, while winter coats grow denser and longer to provide insulation against harsh conditions. Unlike the consistent coloration of species such as the Mexican Fox Squirrel, Least Chipmunks show remarkable color variation within populations.

Sexual dimorphism remains minimal, though males tend to be slightly larger than females during breeding season. Both sexes possess proportionally large cheek pouches that can expand dramatically when filled with seeds—an essential adaptation for their food-hoarding lifestyle in resource-limited environments.

Habitat and Distribution

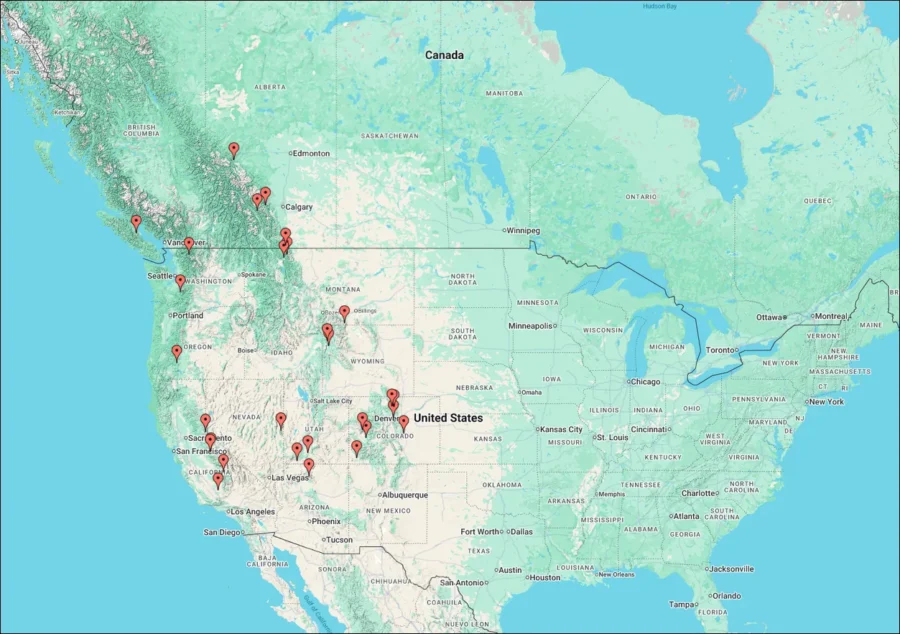

The Least Chipmunk boasts the most extensive distribution of any North American chipmunk species, ranging from the Yukon Territory south to Arizona and New Mexico, and from the Sierra Nevada east to the Great Lakes region. This remarkable range reflects their exceptional adaptability to diverse environmental conditions.

Unlike the forest specialists described in our Complete North American Squirrel Species Guide, Least Chipmunks thrive in multiple ecosystem types. Coniferous forests represent their primary habitat, particularly those dominated by lodgepole pine, Engelmann spruce, and subalpine fir. They show strong preferences for forest edges, clearings, and areas with fallen logs that provide both food sources and protective cover.

Sagebrush communities throughout the Great Basin support substantial Least Chipmunk populations. These arid environments require different survival strategies than forest habitats, with chipmunks utilizing shrub cover and rocky outcrops for denning sites. Their presence in sagebrush ecosystems contrasts sharply with the coniferous forest requirements of species like the Douglas Squirrel.

Alpine and subalpine zones represent some of their most challenging habitats, where they survive at elevations exceeding 12,000 feet. These high-elevation populations demonstrate remarkable cold tolerance and shortened growing season adaptations. They share these extreme environments with few other small mammals, establishing them as true mountain specialists.

Riparian areas provide crucial habitat corridors, particularly in arid regions where water availability limits distribution. Aspen groves, willow thickets, and cottonwood stands offer both food resources and denning opportunities in otherwise unsuitable terrain.

Geographic variations in habitat use reflect local environmental conditions and competitive pressures. Northern populations rely heavily on coniferous forests, while southern populations utilize more diverse habitat types including pinyon-juniper woodlands and montane shrublands.

Territory sizes vary dramatically with elevation and resource availability. High-elevation populations may require larger territories due to limited food resources, while individuals in productive forest habitats maintain smaller, more intensively used areas. Home ranges typically encompass 0.5 to 2 acres, with core activity areas concentrated around primary burrow sites.

Diet and Feeding Behavior

The Least Chipmunk’s dietary flexibility enables their success across diverse ecosystems from alpine meadows to desert shrublands. Their feeding strategies reflect both seasonal resource availability and the need to accumulate winter food caches in environments with extended dormancy periods.

Conifer seeds form the foundation of their diet in forest habitats, with preferences varying by elevation and forest type. Lodgepole pine, whitebark pine, and Engelmann spruce seeds provide essential fats and proteins needed for winter survival. Their specialized cheek pouches allow them to transport hundreds of seeds per foraging trip back to underground storage chambers.

In sagebrush ecosystems, they adapt their diet to available resources including sagebrush leaves, rabbitbrush seeds, and various wildflower seeds. This dietary flexibility contrasts with the more specialized feeding patterns of forest-dependent species covered in our squirrel species guides.

Berries represent crucial seasonal food sources, particularly during late summer when chipmunks build fat reserves for winter dormancy. Huckleberries, serviceberries, and elderberries provide natural sugars and vitamins often scarce in their primary diet. Their berry consumption overlaps with that of larger mammals, though their small size allows access to resources unavailable to bigger competitors.

Green vegetation becomes important during spring and early summer when stored food supplies dwindle and new seed crops haven’t yet matured. They consume grass shoots, wildflower leaves, and young conifer needles to meet nutritional needs during this challenging period.

Insect protein supplements their primarily vegetarian diet, particularly during breeding season when protein demands increase. They hunt beetles, caterpillars, ants, and other small arthropods, occasionally comprising up to 15% of their diet during peak insect abundance periods.

Fungi, including both above-ground mushrooms and underground truffle-like species, provide essential nutrients often lacking in plant foods. Their ability to locate and consume various fungal species gives them access to proteins and minerals crucial for maintaining health in nutrient-poor mountain soils.

Water requirements are met primarily through their food, though they will drink from streams, snowmelt, or dewdrops when available. Their efficient kidney function allows survival in arid environments where surface water remains scarce for extended periods.

Caching behavior represents perhaps their most critical survival adaptation. Individual chipmunks may store 8-10 pounds of food in multiple underground chambers, creating insurance against resource scarcity during their extended winter dormancy. This hoarding strategy differs from the scatter-caching approach used by many tree squirrels.

Reproduction and Life Cycle

Least Chipmunk reproductive biology reflects their adaptation to short growing seasons and harsh environmental conditions. Their breeding strategies ensure offspring arrive during optimal periods for growth and development before winter arrives.

Breeding season timing varies with elevation and latitude, generally occurring from April through July depending on local conditions. High-elevation populations may have extremely compressed breeding windows lasting only 6-8 weeks, while lower elevation populations enjoy more extended seasons.

Mating systems involve promiscuous breeding where both males and females may mate with multiple partners during the breeding season. Males emerge from winter dormancy first, establishing territories and competing for access to females through chase sequences, vocalizations, and scent marking behaviors.

Gestation lasts approximately 30 days, with females giving birth to 2-7 young in underground nest chambers lined with soft plant materials. Litter sizes tend to be smaller at high elevations where resource limitations constrain reproductive investment. Birth timing coincides with peak food availability to ensure adequate maternal nutrition for milk production.

Newborn Least Chipmunks arrive hairless, blind, and completely dependent on maternal care. Their rapid development schedule reflects the compressed growing season available in mountain environments. Eyes open at approximately 28-30 days, and young begin exploring their burrow system shortly afterward.

Weaning occurs at 5-7 weeks, earlier than many other small mammals due to time constraints imposed by short growing seasons. Young chipmunks must rapidly acquire foraging skills and establish food caches before their first winter. This accelerated development schedule contributes to high juvenile mortality rates in challenging years.

Maternal investment varies with environmental conditions and food availability. During abundant years, females may produce second litters, though this is uncommon at high elevations where growing seasons remain too short for successful double brooding.

Sexual maturity arrives during their second year, though some females may breed during their first year if they achieve sufficient body condition. Adult size is typically reached by fall of their first year, though final weight stabilization may not occur until after surviving their first winter.

Survival rates correlate strongly with weather patterns and food availability. Harsh winters or late spring storms can cause significant mortality, particularly among first-year animals lacking experience with extreme conditions. Successful individuals may live 2-5 years in the wild, with maximum recorded lifespans reaching 7 years under optimal conditions.

Behavior and Social Structure

Least Chipmunk social organization centers around individual territories and seasonal activity patterns adapted to extreme environmental conditions. Their behavior reflects the challenges of surviving in habitats where weather conditions can change rapidly and resources may be scarce.

Burrow construction represents a critical survival skill, with systems extending 6-10 feet in length and reaching depths of 3-4 feet underground. These excavations require enormous energy expenditure relative to their body size, but provide essential protection from predators and harsh weather. Multiple entrances allow escape routes and improve ventilation within the burrow system.

Underground chambers serve specialized functions including food storage, nesting, and waste disposal. Cache chambers may contain several pounds of seeds and nuts, representing months of collecting effort. Nest chambers are carefully insulated with plant materials and positioned to maintain optimal temperatures during winter dormancy.

Daily activity patterns follow a bimodal schedule with peak foraging during early morning and late afternoon hours. This timing helps them avoid both midday heat in desert habitats and peak predator activity periods. Unlike the nocturnal flying squirrels such as the Southern Flying Squirrel, Least Chipmunks remain strictly diurnal.

Territorial behavior intensifies during breeding season and food-gathering periods. While generally tolerant of neighbors at territory boundaries, they aggressively defend core areas around their primary burrows and major food caches. Territorial disputes involve chittering vocalizations, tail flicking, and chase sequences.

Communication systems include a variety of vocalizations adapted to their open habitats. Sharp alarm calls warn of aerial predators like hawks and owls, while longer chatter sequences indicate ground-based threats. Their calls often alert other small mammals to danger, creating informal neighborhood watch networks.

Winter dormancy patterns vary with elevation and local climate conditions. High-elevation populations may remain torpid for 6-7 months, while lower elevation individuals experience shorter dormancy periods with periodic winter activity during warm spells. This flexibility in dormancy duration helps them survive unpredictable mountain weather patterns.

Grooming behavior occupies significant portions of their active time, particularly important in dusty or sandy environments where fur condition affects insulation properties. Their flexible spine allows complete body coverage during grooming sessions, while specialized teeth remove debris and parasites.

Climbing abilities exceed those of many ground-dwelling rodents, allowing access to food sources in trees and shrubs. While not as accomplished as arboreal species like the Humboldt’s Flying Squirrel, they readily ascend conifers to harvest seeds and escape ground-based predators.

Interaction with Humans

Least Chipmunks frequently encounter humans throughout their range, particularly in mountainous recreational areas where camping, hiking, and skiing activities overlap with their habitats. Their responses to human presence vary significantly based on previous exposure and local management practices.

In popular camping areas and national parks, some populations become habituated to human presence and may approach campsites seeking food opportunities. While their small size makes them less problematic than larger wildlife, they can cause minor damage by chewing through fabric, accessing stored food, and creating burrows under facilities.

Backcountry encounters typically involve brief sightings as chipmunks quickly retreat to cover when approached. Their natural wariness serves them well in areas with minimal human contact, maintaining wild behavior patterns essential for long-term survival.

Feeding by visitors creates significant problems in recreational areas, leading to population concentrations around developed sites and dependency on human-provided foods. Park managers and forest service personnel actively discourage wildlife feeding through education programs and enforcement activities.

Research opportunities make Least Chipmunks valuable subjects for ecological studies examining climate change impacts, elevation range shifts, and ecosystem responses to environmental changes. Their broad distribution and habitat diversity provide natural experiments for understanding adaptation mechanisms.

Cabin and home interactions occur in mountain communities where development encroaches on natural habitats. Chipmunks may establish burrows under buildings, access stored goods, or utilize bird feeders as food sources. Most conflicts involve minor property damage rather than serious problems.

Educational value stems from their accessibility and interesting behaviors, making them excellent subjects for nature interpretation programs. Their diurnal habits and relative boldness in appropriate settings allow for wildlife viewing opportunities that connect people with mountain ecosystems.

Photography subjects rank among the most popular for wildlife enthusiasts visiting mountain areas. Their photogenic appearance and predictable behavior patterns provide opportunities for capturing natural behaviors without causing significant disturbance to the animals.

Disease concerns remain minimal, as Least Chipmunks rarely carry diseases transmissible to humans. However, they may harbor fleas and ticks that could potentially transmit pathogens, making direct contact inadvisable in areas where vector-borne diseases occur.

Conservation Status

Least Chipmunk populations currently maintain stable status across most of their extensive range, though localized concerns exist in some areas due to habitat changes and climate impacts. Their adaptability and broad distribution provide resilience against many conservation threats.

Climate change represents the most significant long-term challenge for Least Chipmunk populations, particularly those in high-elevation habitats. Warming temperatures may force upslope range shifts, potentially compressing available habitat and increasing competition with other species. Alpine populations face particular vulnerability as suitable habitat becomes increasingly limited.

Habitat fragmentation affects populations in areas experiencing development pressure, particularly in mountain communities and recreational areas. Road construction, ski area development, and residential expansion can isolate populations and reduce habitat quality. However, their small territory requirements and ability to utilize edge habitats provide some resilience against fragmentation.

Forest management practices influence habitat suitability through their effects on forest structure and composition. Clearcutting operations may temporarily benefit chipmunks by creating edge habitats, but extensive logging can eliminate essential cover and food sources. Fire suppression policies that alter natural forest dynamics may also impact long-term habitat quality.

Predation pressure from domestic cats affects populations in areas adjacent to human development. Free-roaming cats pose significant threats to small mammals, with chipmunks representing frequent victims due to their ground-dwelling habits and predictable movement patterns.

Regional population trends vary across their range, with some areas showing stability while others experience declines. Monitoring efforts focus on indicator populations in sensitive habitats, particularly high-elevation sites vulnerable to climate change impacts.

Research priorities include understanding population responses to changing environmental conditions, genetic connectivity between isolated populations, and the effectiveness of different habitat management approaches. Long-term studies tracking population trends provide essential data for conservation planning.

Management recommendations emphasize habitat preservation, connectivity maintenance, and adaptive management strategies that account for changing environmental conditions. Protected area networks play crucial roles in maintaining population viability across their range.

How to Help Least Chipmunks

Supporting Least Chipmunk populations requires understanding their diverse habitat needs and implementing conservation practices appropriate for mountain and arid environments. Individual actions can contribute significantly to their long-term survival, particularly in areas experiencing development pressure.

Habitat protection begins with supporting land conservation efforts in critical areas including high-elevation forests, sagebrush ecosystems, and habitat corridors connecting fragmented populations. Participate in public land management planning processes and advocate for wildlife-friendly policies that maintain habitat connectivity.

Native plant landscaping benefits chipmunks in mountain communities by providing natural food sources and cover. Plant native conifers, shrubs, and wildflowers appropriate for your elevation and climate zone. Avoid non-native ornamental plants that may compete with native species or create ecological imbalances.

Water source management helps during drought periods when natural sources become scarce. Provide shallow water dishes or small dripping sources positioned near natural cover. Maintain these water sources consistently during dry seasons while ensuring they don’t create dependency relationships.

Responsible recreation practices minimize disturbance to chipmunk populations in wilderness and backcountry areas. Follow Leave No Trace principles, avoid feeding wildlife, secure food storage properly, and maintain respectful distances from active burrow sites. Choose established campsites rather than creating new impacts in pristine areas.

Pet management becomes crucial in mountain communities where domestic cats threaten chipmunk populations. Keep cats indoors or in enclosed runs, particularly during breeding and juvenile dispersal seasons. Train dogs to avoid chasing wildlife and maintain leash control in sensitive habitats.

Chemical reduction protects chipmunks from pesticide exposure and habitat contamination. Avoid using rodenticides, herbicides, and insecticides in areas where chipmunks forage. Choose organic gardening methods and biological pest controls that don’t threaten non-target species.

Citizen science participation provides valuable data for conservation research. Report chipmunk sightings to wildlife agencies, participate in population monitoring programs, and document behavioral observations. Photography and detailed location records help researchers understand distribution patterns and population trends.

Education and outreach extend conservation benefits beyond individual properties. Share information about chipmunk ecology with fellow outdoor enthusiasts, support environmental education programs, and advocate for wildlife-friendly development practices in mountain communities.

Climate action addresses the most significant long-term threat facing high-elevation populations. Support renewable energy initiatives, reduce personal carbon footprints, and advocate for policies addressing climate change impacts on mountain ecosystems.

Injured wildlife assistance requires contacting licensed wildlife rehabilitators rather than attempting home care. These professionals have the training and permits necessary for proper treatment and release. Observe injured animals from a distance while arranging professional help and keep domestic animals away from the area.

Seasonal considerations include avoiding major landscape disturbances during breeding season and winter dormancy periods. Spring and early summer represent critical times when human activities can most significantly impact chipmunk success, while winter disturbances may force premature emergence from torpor.

Conclusion

The Least Chipmunk stands as one of North America’s most remarkable small mammal success stories, demonstrating extraordinary adaptability across diverse mountain and desert environments. Their ability to thrive from sagebrush flats to alpine peaks showcases evolutionary flexibility that enables survival in some of the continent’s most challenging habitats.

Understanding Least Chipmunk ecology reveals complex relationships between elevation, climate, and survival strategies. Their sophisticated food caching systems, flexible dormancy patterns, and dietary adaptability represent solutions to environmental challenges that few other small mammals can match. These adaptations position them as indicators of ecosystem health across their vast range.

As climate change continues to reshape mountain environments, the Least Chipmunk’s future depends on maintaining habitat connectivity and supporting adaptive management strategies. Their current success provides optimism for conservation efforts, though continued monitoring and protection remain essential for long-term population viability.

The species’ broad distribution and ecological flexibility offer valuable lessons about wildlife conservation in an era of rapid environmental change. By understanding and supporting their habitat needs, we contribute to preserving not only chipmunk populations but entire mountain and desert ecosystems that depend on their ecological services.

Future research and conservation efforts should focus on understanding population responses to changing environmental conditions while maintaining the habitat diversity that supports their remarkable adaptability. Through informed stewardship, we can ensure that these charismatic mountain dwellers continue to thrive across North America’s most spectacular landscapes.

Their presence enriches our wilderness experiences and connects us to the intricate web of life that makes mountain ecosystems so remarkable. By appreciating and protecting Least Chipmunks, we invest in the health and diversity of the natural world that sustains us all.