The forest falls silent as dusk settles over the North American wilderness. High in the canopy, a shadow glides between towering conifers—not a bird, but something far more mysterious. With outstretched membranes catching the evening air, the Northern Flying Squirrel begins its nocturnal journey, a creature so elusive that most people never witness its graceful flight through the darkness.

The Northern Flying Squirrel (Glaucomys sabrinus) is North America’s largest flying squirrel, distinguished by its silky fur, large dark eyes, and gliding membrane that stretches between its limbs, enabling glides of up to 150 feet between trees.

Quick Facts

| Attribute | Details |

|---|---|

| Scientific Name | Glaucomys sabrinus |

| Size | 10-14 inches body length, 5-7 inches tail |

| Weight | 75-180 grams (2-6 ounces) |

| Lifespan | 4-5 years wild, up to 13 years captivity |

| Habitat | Coniferous and mixed forests, mature canopy |

| Diet | Specialist: fungi, nuts, seeds, insects, bird eggs |

| Activity | Nocturnal (peak activity after sunset and before dawn) |

| Conservation Status | Least Concern (some subspecies endangered) |

Physical Description

The Northern Flying Squirrel represents one of nature’s most remarkable adaptations for arboreal life. These extraordinary mammals possess a unique gliding membrane called a patagium that extends from their wrists to their ankles, creating a living parachute that enables them to soar through forest canopies with remarkable precision.

Their dense, silky fur provides essential insulation against harsh northern climates, with coloration ranging from rich cinnamon-brown to grayish-brown on their backs, while their bellies display a pristine white or cream coloration. This fur quality distinguishes them significantly from other squirrel species found in our Complete North American Squirrel Species Guide, as their coat remains consistently soft and luxurious throughout the year.

Their most striking feature remains their oversized, dark eyes—perfectly adapted for their nocturnal lifestyle. These large, prominent eyes contain specialized cells that gather available light, allowing them to navigate through darkness with exceptional accuracy. Unlike diurnal species such as the Eastern Gray Squirrel, Northern Flying Squirrels have evolved to see clearly in low-light conditions that would render other squirrels nearly blind.

The patagium itself represents a marvel of evolutionary engineering. This stretched membrane of skin and fur extends along the sides of their body, supported by a cartilaginous spur extending from each wrist. When gliding, they spread their limbs wide, transforming their body into an efficient airfoil capable of controlled flight. Their flat, densely-furred tail serves as both rudder and brake, allowing for precision landings and directional changes mid-flight.

Body proportions differ markedly from ground-dwelling squirrels, with relatively longer limbs and a more streamlined build optimized for gliding rather than running. Their feet feature sharp, curved claws perfectly designed for gripping bark and maintaining secure holds on vertical surfaces, while their lightweight bone structure reduces overall body weight without sacrificing strength.

Habitat and Distribution

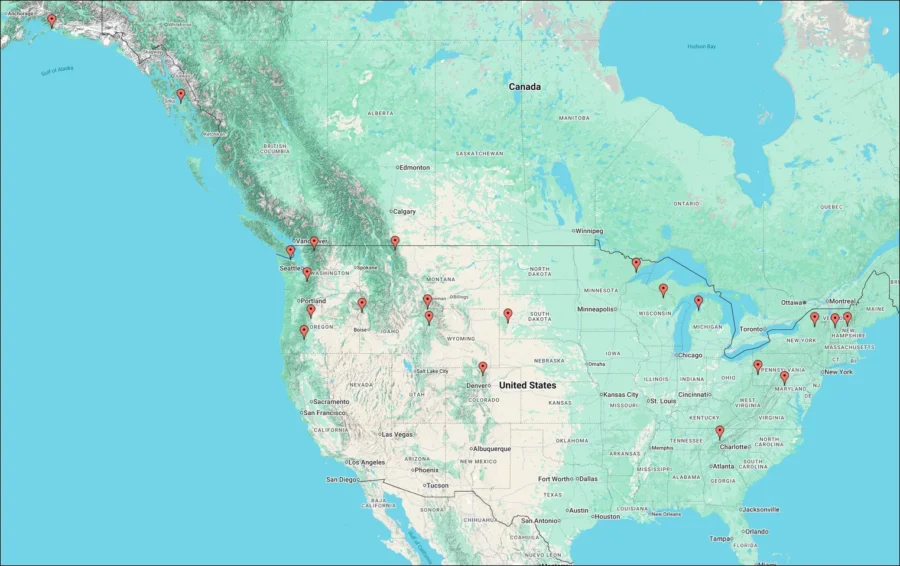

Northern Flying Squirrels inhabit some of North America’s most pristine wilderness areas, showing a strong preference for mature coniferous and mixed forests that provide the complex three-dimensional environment necessary for their gliding lifestyle. Their distribution extends across the boreal forests of Alaska and Canada, with populations extending south through the Rocky Mountains, Pacific Northwest, and scattered populations in the northern Great Lakes region and Appalachian Mountains.

These remarkable creatures require forests with specific characteristics that distinguish their habitat needs from other North American squirrel species. They favor areas with dense canopy cover that provides continuous travel routes between trees, as gaps larger than 150 feet present significant barriers to their movement. Old-growth forests with large trees, multiple canopy layers, and abundant dead wood provide ideal conditions, as these environments support the complex fungal communities that form a crucial part of their diet.

Temperature and elevation play crucial roles in their distribution patterns. Northern Flying Squirrels thrive in cooler climates and can be found at elevations ranging from sea level in northern regions to over 10,000 feet in mountainous areas. Their dense fur and efficient metabolism allow them to remain active throughout winter, unlike some other squirrel species that enter periods of reduced activity during harsh weather.

Forest composition heavily influences their presence, with western populations showing strong associations with Douglas fir, western hemlock, and true fir forests, while eastern populations prefer spruce-fir forests and mixed deciduous-coniferous woodlands. The presence of hypogeous fungi—underground mushrooms that fruit beneath the soil surface—often determines habitat suitability, as these fungi comprise up to 80% of their diet in some regions.

Human activities have significantly impacted their distribution, with logging, forest fragmentation, and development creating barriers to movement and reducing suitable habitat. Climate change poses additional challenges, as warming temperatures may shift suitable habitat ranges northward and to higher elevations, potentially isolating populations and reducing genetic diversity.

Diet and Feeding Behavior

The Northern Flying Squirrel exhibits one of the most specialized diets among North American squirrels, with their feeding behavior centered around an extraordinary relationship with fungi that sets them apart from species like the Fox Squirrel or American Red Squirrel, which rely more heavily on nuts and seeds.

Hypogeous fungi, commonly known as truffles, constitute the cornerstone of their diet throughout much of their range. These underground mushrooms form symbiotic relationships with tree roots, creating networks that benefit forest health. Northern Flying Squirrels locate these buried treasures using their exceptional sense of smell, often digging through several inches of soil and forest litter to reach their fungal prey. This behavior makes them crucial dispersers of fungal spores, as the spores pass through their digestive system and are deposited throughout the forest in their droppings.

Seasonal variation significantly influences their dietary patterns. During spring and early summer, when fungi are less abundant, they supplement their diet with tree buds, flowers, and emerging vegetation. Protein requirements increase during breeding season, leading to increased consumption of insects, bird eggs, and occasionally nestling birds. Late summer and fall bring abundant seed crops from conifers, which they cache extensively for winter survival.

Their feeding schedule aligns with their nocturnal nature, with peak activity occurring during the first few hours after sunset and again before dawn. This timing minimizes competition with diurnal species and reduces predation risk while allowing them to exploit food sources that may be less accessible during daylight hours.

Winter feeding presents unique challenges that demonstrate their remarkable adaptability. When fresh fungi become scarce, they rely heavily on cached seeds and bark. Their ability to locate food caches beneath snow demonstrates exceptional spatial memory, often finding buried caches weeks or months after storing them. During severe weather, they may enter brief periods of reduced activity but never hibernate like some ground squirrels.

Food storage behavior differs markedly from other squirrel species, with Northern Flying Squirrels showing less extensive caching behavior than species like the Douglas Squirrel. Instead, they rely more on immediate consumption and community food sharing, particularly during harsh weather when multiple individuals may share resources.

Reproduction and Life Cycle

Northern Flying Squirrels follow a reproductive pattern that reflects their adaptation to harsh northern climates, with breeding cycles timed to ensure young are born during optimal conditions for survival. Their reproductive biology demonstrates remarkable synchronization with environmental conditions, ensuring maximum survival rates for their offspring.

Breeding season typically occurs once yearly, beginning in late winter or early spring, with exact timing varying by latitude and local climate conditions. In northern populations, mating occurs between March and May, while southern populations may breed as early as February. Males become more active during this period, engaging in extended gliding flights as they search for receptive females across their territories.

Gestation lasts approximately 37-42 days, with females giving birth to litters of 2-4 young in tree cavities or specialized nests. These birth sites are carefully selected for protection from predators and weather, often located in mature trees with natural hollows or abandoned woodpecker holes. The female constructs elaborate nests using shredded bark, moss, and other soft materials, creating a warm, insulated environment crucial for the survival of their altricial young.

Newborn Northern Flying Squirrels are born blind, hairless, and completely dependent on maternal care. Their eyes open at approximately 31-35 days, and they begin developing their characteristic gliding membrane shortly thereafter. The development of gliding ability represents a critical milestone, as young must master this skill before becoming independent.

Weaning occurs at 6-8 weeks, but juveniles often remain with their mother for several additional weeks, learning essential survival skills including gliding techniques, food location, and predator avoidance. During this period, family groups may share nests and food resources, with mothers actively teaching their young to identify suitable fungi and navigate through the forest canopy.

Sexual maturity is reached at approximately one year of age, though many individuals may not breed until their second year, particularly in northern populations where environmental conditions are more challenging. This delayed reproduction ensures that individuals have sufficient time to develop the skills and knowledge necessary for successful breeding.

Parental investment extends beyond basic care, with mothers continuing to provide guidance and occasionally sharing food resources with their offspring well into their first winter. This extended care period contributes to higher survival rates compared to other small mammals, though mortality remains significant due to predation and environmental factors.

Behavior and Social Structure

Northern Flying Squirrels exhibit complex social behaviors that distinguish them from many other squirrel species, showing remarkable adaptability in their social organization based on environmental conditions and resource availability. Their behavioral patterns reflect sophisticated adaptations to nocturnal life and the challenges of surviving in harsh northern climates.

Unlike the more territorial nature of species such as the American Red Squirrel, Northern Flying Squirrels demonstrate considerable social flexibility. During favorable conditions, they maintain loose territories with overlapping home ranges, allowing for peaceful coexistence and resource sharing. However, during harsh winter conditions, their social structure becomes more cooperative, with multiple individuals sharing nests and body heat for survival.

Communal nesting represents one of their most remarkable behavioral adaptations. Groups of 3-8 individuals may share a single nest cavity during extreme cold, huddling together to conserve body heat and reduce energy expenditure. These temporary aggregations typically consist of related individuals, though unrelated animals may also join communal groups when conditions warrant. This behavior demonstrates a level of social cooperation rarely seen in other North American squirrel species.

Their gliding behavior showcases remarkable precision and control, with individuals capable of adjusting their flight path mid-air using subtle movements of their tail and limbs. Gliding serves multiple functions beyond simple transportation, including predator escape, efficient foraging, and territorial displays. Young individuals spend considerable time practicing gliding techniques, often making short practice flights between nearby branches before attempting longer distances.

Communication among Northern Flying Squirrels involves a complex array of vocalizations, scent marking, and tactile behaviors. Their vocal repertoire includes soft chirps, clicks, and chattering sounds that serve different functions including mate attraction, territory defense, and alarm calls. Scent marking using specialized glands helps establish territories and communicate reproductive status, while tactile communication through grooming and physical contact reinforces social bonds within family groups.

Activity patterns are strictly nocturnal, with peak activity occurring during the darkest hours of night. This timing reduces competition with diurnal species and minimizes predation risk from visual predators. Their large eyes and sensitive hearing allow them to navigate effectively in complete darkness, while their soft fur enables nearly silent movement through the forest canopy.

Territorial behavior varies seasonally, with more defined territories during breeding season and more flexible boundaries during winter months. Home ranges typically encompass 1-5 acres, depending on food availability and forest structure, with individuals maintaining detailed mental maps of their territory including the location of nest sites, food caches, and travel routes.

Interaction with Humans

The relationship between Northern Flying Squirrels and humans represents a complex dynamic shaped by habitat overlap, conservation concerns, and the species’ secretive nature. Unlike more visible species such as the Eastern Gray Squirrel or Western Gray Squirrel, most people never encounter Northern Flying Squirrels due to their nocturnal habits and preference for remote forest environments.

Human activities have profoundly impacted Northern Flying Squirrel populations through habitat modification and fragmentation. Logging practices, particularly clear-cutting and the removal of old-growth forests, eliminate the complex canopy structure essential for their survival. Forest fragmentation creates gaps too large for gliding, effectively isolating populations and reducing genetic diversity. Urban development further compounds these challenges by creating permanent barriers to movement and eliminating crucial habitat corridors.

Climate change presents emerging challenges that may reshape the relationship between humans and these remarkable creatures. Warming temperatures are shifting suitable habitat ranges northward and to higher elevations, potentially reducing available habitat and increasing competition with other species. Forest management practices are evolving to address these challenges, with increased emphasis on maintaining connectivity and preserving old-growth characteristics.

Research efforts have revealed the critical ecological role these squirrels play as fungal spore dispersers, making them keystone species in forest ecosystems. This discovery has elevated their importance in forest management planning and conservation strategies. Scientists continue studying their behavior using radio telemetry and other tracking methods, providing insights that inform habitat management decisions.

Educational outreach programs help raise awareness about Northern Flying Squirrels and their conservation needs. Many people are surprised to learn that flying squirrels exist in North America, as their secretive nature and nocturnal habits make them nearly invisible to casual observers. Nature centers and wildlife organizations work to educate the public about their ecological importance and the threats they face.

Occasionally, Northern Flying Squirrels may establish nests in human structures, particularly in rural areas where buildings are surrounded by suitable forest habitat. Unlike other squirrel species that may cause significant damage, flying squirrels typically create minimal disturbance and may even provide benefits through insect control. However, their presence often goes unnoticed due to their quiet nature and nocturnal activity patterns.

Conservation Status and Threats

The conservation status of Northern Flying Squirrels varies significantly across their range, with some populations thriving while others face serious threats that have led to protected status under endangered species legislation. Understanding these regional differences is crucial for developing effective conservation strategies that address the specific challenges facing different populations.

Overall, the species is classified as Least Concern by international conservation organizations, reflecting their wide distribution and relatively stable populations across much of their range. However, this broad classification masks significant regional variations, with several subspecies and isolated populations facing severe threats that warrant special conservation attention.

The Carolina Northern Flying Squirrel (Glaucomys sabrinus coloratus) represents the most critically threatened population, listed as Endangered under the U.S. Endangered Species Act. This subspecies is restricted to high-elevation spruce-fir forests in the southern Appalachian Mountains, where habitat loss, fragmentation, and climate change have reduced populations to critically low levels. Competition with the more adaptable Eastern Gray Squirrel further compounds conservation challenges in these areas.

West Virginia Northern Flying Squirrels face similar challenges, with populations restricted to high-elevation areas where suitable habitat continues to decline. Forest management practices, including logging and development, have fragmented their habitat and reduced the availability of old-growth forest characteristics essential for their survival.

Primary threats across their range include habitat loss and fragmentation from logging, development, and forest management practices that prioritize timber production over ecosystem integrity. The removal of old-growth forests eliminates the complex habitat structure and fungal communities that Northern Flying Squirrels require for survival. Even selective logging can significantly impact populations by removing key nest trees and disrupting canopy connectivity.

Climate change poses an increasingly significant threat, particularly for southern populations already living at the limits of their thermal tolerance. Rising temperatures are shifting suitable habitat to higher elevations and northern latitudes, potentially reducing available habitat and isolating populations. Changes in precipitation patterns may also affect the fungal communities that form the foundation of their diet.

Competition with other species, particularly the expanding ranges of Eastern Gray Squirrels, presents additional challenges in some areas. Gray squirrels are more adaptable to disturbed habitats and may outcompete flying squirrels for nest sites and food resources in fragmented landscapes.

Disease represents an emerging threat, with some populations experiencing mortality from parasites and pathogens that may be exacerbated by habitat stress and climate change. Research is ongoing to understand the impacts of various diseases on population dynamics and survival rates.

Conservation efforts focus on habitat protection and restoration, with emphasis on maintaining large blocks of suitable forest and ensuring connectivity between populations. Forest management practices are being modified to retain old-growth characteristics, including snags, large trees, and complex canopy structure. Protected areas play a crucial role in conservation, providing refugia where populations can persist without human interference.

How to Help Northern Flying Squirrels

Supporting Northern Flying Squirrel conservation requires a multifaceted approach that addresses their unique habitat needs and the specific threats they face. Whether you’re a landowner, outdoor enthusiast, or concerned citizen, there are numerous ways to contribute to the protection and recovery of these remarkable creatures.

Habitat Protection and Enhancement

If you own forested property within Northern Flying Squirrel range, consider implementing forest management practices that benefit these species. Maintain mature trees with natural cavities or install nest boxes specifically designed for flying squirrels. These artificial nest sites can supplement natural cavities and provide secure breeding locations, particularly in areas where suitable trees are scarce.

Preserve dead trees (snags) whenever safely possible, as these provide essential nesting sites and support the insects that form part of their diet. Create or maintain corridors of continuous canopy cover to facilitate movement between forest patches, as gaps larger than 150 feet present significant barriers to their gliding locomotion.

Supporting Fungal Communities

Protect and encourage the growth of mycorrhizal fungi that form the foundation of Northern Flying Squirrel diets. Avoid the use of fungicides and minimize soil disturbance in forested areas. Leave fallen logs and organic debris on the forest floor, as these provide substrate for fungal growth and maintain the complex forest ecosystem that flying squirrels depend upon.

Citizen Science and Monitoring

Participate in citizen science programs that monitor Northern Flying Squirrel populations and habitat. Many wildlife agencies and research organizations rely on volunteers to help survey populations and gather data on distribution patterns. Report any sightings to local wildlife agencies or naturalist organizations, as every observation contributes to our understanding of their current status and distribution.

Advocating for Conservation Policy

Support legislation and policies that protect old-growth forests and promote sustainable forest management practices. Contact your representatives about the importance of maintaining habitat connectivity and supporting endangered subspecies recovery programs. Advocate for funding of research programs that study Northern Flying Squirrel ecology and conservation needs.

Educational Outreach

Share your knowledge about Northern Flying Squirrels with others, helping to raise awareness about these secretive and remarkable creatures. Many people are unaware that flying squirrels exist in North America, and education is the first step toward building public support for conservation efforts.

Support organizations working to protect Northern Flying Squirrels and their habitat through donations or volunteer work. Many conservation groups, zoos, and research institutions are actively involved in flying squirrel research and habitat protection programs.

Responsible Recreation

When recreating in Northern Flying Squirrel habitat, follow Leave No Trace principles and avoid disturbing potential nesting sites. Keep noise to a minimum during dawn and dusk hours when flying squirrels are most active, and use designated trails to minimize habitat disturbance.

Creating Wildlife-Friendly Landscapes

Even in suburban areas, you can create conditions that support the broader ecosystem that Northern Flying Squirrels depend upon. Plant native trees and shrubs, reduce the use of pesticides and herbicides, and maintain natural areas that provide stepping stones for wildlife movement.

Conclusion

The Northern Flying Squirrel stands as one of North America’s most extraordinary and specialized mammals, embodying millions of years of evolutionary adaptation to life in the forest canopy. Their remarkable gliding abilities, sophisticated social behaviors, and crucial ecological role as fungal spore dispersers make them keystone species in northern forest ecosystems. Yet their secretive nature and specific habitat requirements also make them vulnerable to the rapid environmental changes of the modern world.

As we’ve explored throughout this comprehensive guide, Northern Flying Squirrels face an uncertain future marked by habitat loss, climate change, and increasing human pressure on the wild spaces they call home. Some populations, like the Carolina Northern Flying Squirrel, teeter on the brink of extinction, while others maintain stable numbers across vast wilderness areas. This variation reminds us that conservation success requires attention to local conditions and specific population needs.

The story of the Northern Flying Squirrel is ultimately a story about the intricate connections that bind forest ecosystems together. Their dependence on fungi, their role in forest regeneration, and their position in the food web demonstrate how the loss of a single species can cascade through entire ecosystems. Understanding these connections, as outlined in our Complete North American Squirrel Species Guide, helps us appreciate the complexity of conservation challenges and the importance of protecting entire ecosystems rather than individual species in isolation.

The future of Northern Flying Squirrels depends on our collective commitment to protecting the mature forests they require and addressing the broader environmental challenges that threaten their survival. Through informed forest management, habitat protection, citizen science participation, and continued research, we can work to ensure that future generations will have the opportunity to witness the silent grace of these remarkable gliders as they navigate through the darkened forest canopy.

Every action we take to protect Northern Flying Squirrels also benefits the countless other species that share their forest home, from the towering trees that form their highways to the microscopic fungi that sustain them. In protecting these aerial acrobats, we preserve not just a species, but an entire way of life that has persisted in North America’s forests for millennia.