A warm summer evening blankets the eastern woodlands as twilight transforms the forest into a realm of shadows and whispers. In the gathering darkness, a tiny silhouette launches from an ancient oak, spreading its furry parachute against the starlit sky. The Southern Flying Squirrel begins its nightly dance through the canopy, a pint-sized acrobat whose gentle presence brings magic to North America’s deciduous forests.

The Southern Flying Squirrel (Glaucomys volans) is North America’s smallest flying squirrel, characterized by its diminutive size, large dark eyes, and silky gray-brown fur, capable of gliding up to 80 feet between trees using its specialized patagium membrane.

| Attribute | Details |

|---|---|

| Scientific Name | Glaucomys volans |

| Size | 8-10 inches body length, 3-5 inches tail |

| Weight | 45-85 grams (1.5-3 ounces) |

| Lifespan | 3-5 years wild, up to 10 years captivity |

| Habitat | Deciduous and mixed forests, woodlands |

| Diet | Omnivorous: nuts, seeds, fruits, insects, bird eggs |

| Activity | Nocturnal (most active 1-3 hours after sunset) |

| Conservation Status | Least Concern (stable populations) |

Physical Description

The Southern Flying Squirrel represents nature’s most diminutive gliding mammal in North America, possessing an enchanting combination of delicate features and remarkable aerial adaptations that distinguish it from all other members of our Complete North American Squirrel Species Guide. These tiny acrobats embody evolutionary perfection in miniature form, with every aspect of their anatomy refined for life among the treetops.

Their most immediately striking feature consists of enormous, liquid-dark eyes that dominate their small faces, appearing almost cartoonishly large in proportion to their petite skulls. These oversized eyes contain specialized retinal adaptations that gather available light with exceptional efficiency, enabling them to navigate through complete darkness with remarkable precision. Unlike diurnal species such as the Eastern Gray Squirrel, their eyes remain constantly moist and reflective, creating an almost luminous appearance in low light conditions.

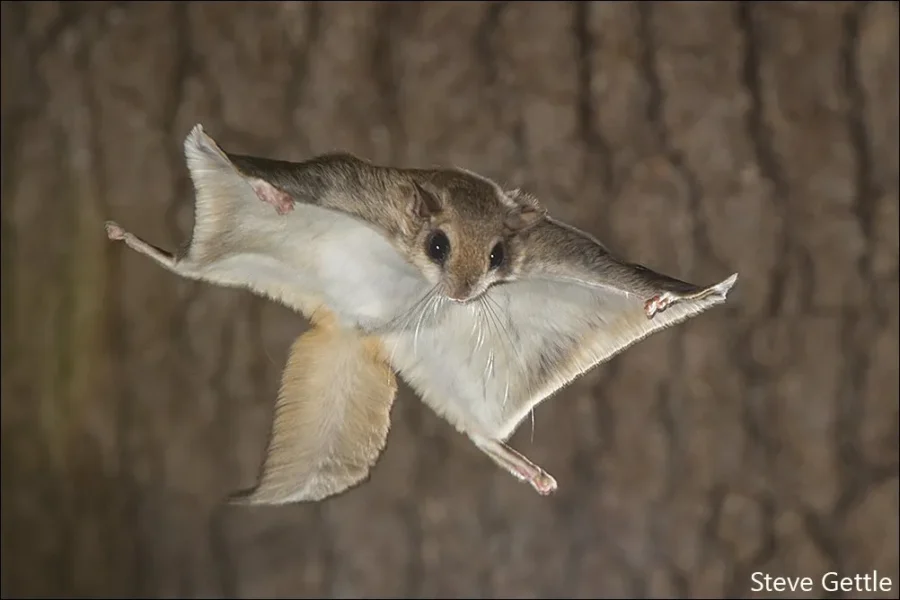

The patagium, their signature gliding membrane, stretches from wrist to ankle along each side of their body, creating a living parachute when extended. This remarkable adaptation consists of a double layer of furred skin supported by a cartilaginous rod extending from each wrist, allowing for precise control during gliding maneuvers. When not in use, the patagium folds neatly against their body, creating minimal interference during climbing or running activities.

Their fur quality surpasses that of most other squirrel species, featuring an incredibly soft, dense coat that provides both insulation and aerodynamic properties. The dorsal coloration ranges from pale gray-brown to rich cinnamon, while their ventral surface displays pristine white or cream coloring that extends from chin to tail. This fur remains consistently silky throughout the year, lacking the coarser guard hairs found in larger squirrel species.

Body proportions reflect their specialized lifestyle, with relatively long limbs and a flattened tail that serves as both rudder and brake during gliding. Their lightweight bone structure reduces overall body weight without sacrificing strength, while their small size allows them to utilize the finest branches and twigs that would not support larger animals. Sharp, curved claws provide exceptional gripping ability on bark surfaces, enabling them to land securely even on smooth-barked trees.

Sexual dimorphism remains minimal, though males typically measure slightly larger than females and may display more prominent scent glands during breeding season. Both sexes possess the same remarkable gliding capabilities and physical adaptations that make them such successful arboreal specialists.

Habitat and Distribution

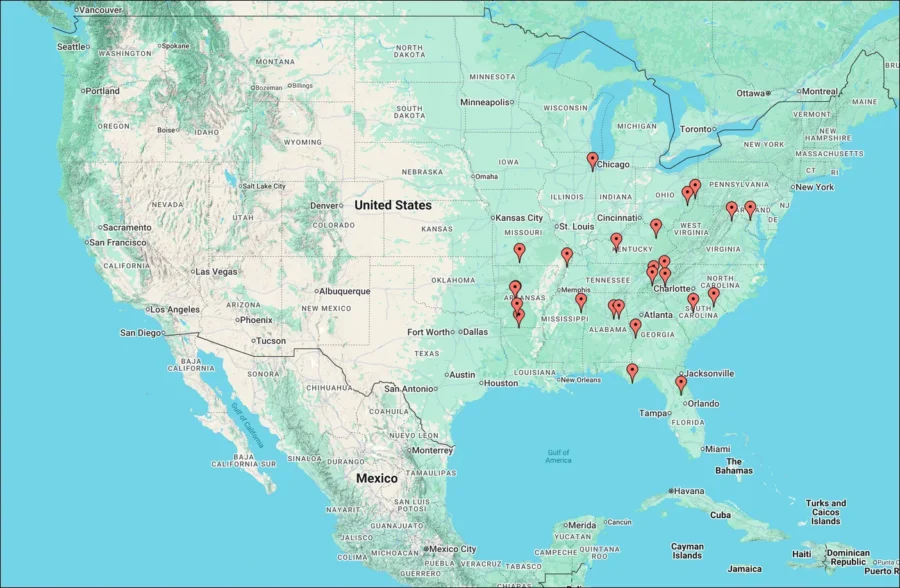

Southern Flying Squirrels inhabit the largest geographic range of any flying squirrel species in North America, demonstrating remarkable adaptability to diverse forest types across the eastern United States, southeastern Canada, and portions of Central America. Their distribution extends from southern Maine and southern Ontario south to Florida and west to Minnesota and eastern Texas, with isolated populations in Mexico and Central America representing the southernmost extent of flying squirrel range in the Western Hemisphere.

These adaptable creatures show strong preferences for deciduous and mixed forests that provide the complex three-dimensional habitat structure essential for their gliding lifestyle. Unlike their northern cousins, Southern Flying Squirrels thrive in a variety of forest types, including oak-hickory forests, maple-beech woodlands, pine-hardwood mixtures, and even mature suburban woodlots that retain sufficient canopy cover and connectivity.

Elevation preferences vary significantly across their range, from sea level in coastal areas to over 4,500 feet in the Appalachian Mountains. Their adaptability to different elevations and climate conditions has contributed to their successful colonization of diverse habitats, making them far more widespread than the more specialized Northern Flying Squirrel that requires specific coniferous forest conditions.

Forest structure plays a more critical role than specific tree species composition in determining habitat suitability. Southern Flying Squirrels require continuous or nearly continuous canopy cover that enables gliding between trees, with gaps larger than 50-80 feet presenting significant barriers to movement. Mature forests with multiple canopy layers provide optimal conditions, offering diverse food sources, numerous nesting sites, and protection from predators.

Edge habitats where forests meet clearings or water bodies often support high densities of Southern Flying Squirrels, as these areas typically provide enhanced food diversity and nesting opportunities. However, extensive fragmentation can isolate populations and reduce genetic diversity, particularly in agricultural landscapes where forest patches become increasingly isolated.

Seasonal habitat use patterns reflect their dietary needs and reproductive cycles. During spring and summer, they show preferences for areas with abundant insect populations and fruiting trees, while fall habitat selection focuses on locations with heavy mast production from oaks, hickories, and other nut-producing species. Winter habitat requirements emphasize areas with suitable den sites and cached food resources.

Human-modified landscapes can support Southern Flying Squirrel populations when sufficient forest cover remains. Suburban areas with mature trees, parks, and greenbelts often maintain viable populations, though these habitats typically support lower densities than continuous forest environments. Their tolerance for human proximity, combined with their nocturnal habits, allows them to persist in areas where other wildlife species have disappeared.

Diet and Feeding Behavior

Southern Flying Squirrels exhibit one of the most diverse and opportunistic feeding strategies among North American squirrel species, demonstrating remarkable dietary flexibility that has contributed to their widespread distribution and ecological success. Their omnivorous diet varies dramatically with seasonal food availability, geographic location, and local forest composition, setting them apart from more specialized species like the American Red Squirrel with its focus on conifer seeds.

Tree nuts form the foundation of their diet during fall and winter months, with acorns, hickory nuts, walnuts, and beechnuts providing essential fats and proteins needed for winter survival. Their small size allows them to access nuts that larger squirrels cannot reach, while their exceptional spatial memory enables them to relocate cached food sources weeks or months after storage. Unlike the more extensive caching behavior of Fox Squirrels, Southern Flying Squirrels typically cache smaller quantities in numerous scattered locations.

Insects comprise a significant portion of their diet, particularly during spring and summer when protein requirements increase for reproduction and growth. They actively hunt moths, beetles, caterpillars, and other insects, using their exceptional night vision and agility to capture prey both in flight and on bark surfaces. Their insectivorous habits make them valuable allies in forest pest control, consuming significant quantities of insects that might otherwise damage trees.

Seasonal fruits and berries provide essential vitamins and carbohydrates throughout the growing season. Wild cherries, dogwood berries, sumac fruits, and various woodland berries feature prominently in their summer diet, while they may also consume cultivated fruits in areas near human habitation. Their small size allows them to reach fruits on branches too delicate for larger animals.

Tree buds, flowers, and bark constitute important food sources during lean periods, particularly in early spring when stored nuts become depleted and new growth provides the first fresh nutrition of the year. They show remarkable selectivity in choosing the most nutritious plant parts, often focusing on sugar-rich sap sources and protein-rich flower parts.

Bird eggs and nestlings occasionally supplement their diet during breeding season, though this represents a smaller proportion of their food intake compared to some other squirrel species. Their exceptional climbing ability allows them access to nests in the finest branches where other predators cannot reach, though they typically focus on smaller songbird species.

Fungi, while less important than for Northern Flying Squirrels, still play a role in their diet, particularly mushrooms and other above-ground fungal fruiting bodies. They show less specialization in fungal consumption compared to their northern relatives, reflecting the greater diversity of alternative food sources in deciduous forest environments.

Feeding activity follows strict nocturnal patterns, with peak foraging occurring during the first 2-3 hours after sunset and again in the pre-dawn hours. This timing minimizes competition with diurnal species and reduces predation risk while allowing them to exploit food sources that may be less accessible during daylight hours.

Reproduction and Life Cycle

Southern Flying Squirrels demonstrate a reproductive strategy that maximizes their potential for population growth and range expansion, with many populations capable of producing two litters per year under favorable conditions. This enhanced reproductive capacity distinguishes them from their northern relatives and contributes to their more stable population status across most of their range.

The breeding season extends considerably longer than that of most other squirrel species, typically beginning in late winter and continuing through early fall, with two distinct peaks corresponding to optimal conditions for offspring survival. The first breeding period occurs from February through April, while a second breeding season takes place from June through August, allowing successful females to potentially double their annual reproductive output.

Mating behaviors involve elaborate aerial courtship displays that showcase the remarkable gliding abilities of both sexes. Males become increasingly active during breeding periods, engaging in extended flights as they search for receptive females across expanded territories. Courtship chases through the canopy demonstrate remarkable aerial agility, with pairs spiraling around tree trunks and making rapid direction changes that would challenge even the most skilled pilots.

Gestation lasts approximately 40 days, with females selecting carefully concealed nesting sites in tree cavities, abandoned woodpecker holes, or elaborate leaf nests constructed in dense foliage. These birth sites receive meticulous preparation, with females gathering soft materials including shredded bark, moss, feathers, and fur to create insulated environments crucial for the survival of their altricial young.

Litter sizes typically range from 2-4 young, though larger litters of up to 6 individuals have been recorded under exceptionally favorable conditions. Newborns are born completely helpless, weighing less than 5 grams and measuring only about 2 inches in length. Their eyes remain closed for approximately 4-5 weeks, and the characteristic gliding membrane doesn’t fully develop until they approach weaning age.

Maternal care extends beyond basic nursing, with mothers actively teaching essential survival skills including gliding techniques, food identification, and predator recognition. Young flying squirrels make their first tentative gliding attempts at 6-7 weeks of age, initially covering short distances between adjacent branches before gradually building confidence and skill for longer flights.

Weaning occurs at approximately 8-10 weeks, though family groups often remain together for several additional weeks as juveniles continue learning from their mother and siblings. This extended family association contributes to higher survival rates and helps establish social connections that may persist into adulthood.

Sexual maturity is typically reached during their first year, though many individuals postpone breeding until their second year, particularly those born late in the season. This flexibility in reproductive timing allows populations to respond rapidly to favorable conditions while avoiding reproduction during stressful periods.

The potential for two annual litters provides Southern Flying Squirrels with significant reproductive advantages, allowing populations to recover quickly from periodic setbacks and expand into newly available habitat more rapidly than single-brooded species.

Behavior and Social Structure

Southern Flying Squirrels exhibit complex social behaviors that reflect both their evolutionary history as communal creatures and their adaptations to diverse environmental challenges across their extensive range. Their behavioral flexibility has undoubtedly contributed to their success as the most widespread flying squirrel species in North America, demonstrating social strategies that range from solitary territoriality to cooperative group living depending on local conditions and resource availability.

Social organization varies significantly with season, population density, and resource distribution, creating a dynamic system that maximizes survival under changing conditions. During summer months when food is abundant and weather is favorable, individuals typically maintain loosely defined territories with considerable overlap, allowing for peaceful coexistence and resource sharing among neighbors. This flexible territoriality contrasts sharply with the more rigid territorial systems of species like the American Red Squirrel.

Winter aggregation behaviors represent one of their most remarkable social adaptations, with groups of 10-20 individuals sometimes sharing single nest cavities during extreme cold periods. These temporary communities form based on kinship relationships, established social bonds, and simple proximity, with unrelated individuals readily joining existing groups when conditions warrant. Communal nesting provides crucial thermoregulatory benefits, allowing small-bodied animals to maintain body temperature during harsh weather that might otherwise prove lethal.

Gliding behavior serves multiple social functions beyond simple locomotion, including territorial displays, courtship demonstrations, and escape responses. Their gliding technique demonstrates remarkable precision, with individuals capable of making 90-degree turns mid-flight and landing with pinpoint accuracy on branches as small as pencil thickness. Young individuals spend considerable time practicing these skills, often engaging in playful gliding games that help develop the aerial proficiency essential for adult survival.

Communication among Southern Flying Squirrels involves a surprisingly complex array of vocalizations, scent marking, and tactile behaviors that facilitate social coordination and territory management. Their vocal repertoire includes soft chirps, clicks, chattering sounds, and even ultrasonic calls that may serve specialized communication functions. These vocalizations vary in intensity and frequency based on context, with alarm calls, mating calls, and social contact calls each serving distinct purposes.

Scent marking plays a crucial role in social organization, with specialized glands producing chemical signals that communicate reproductive status, individual identity, and territorial boundaries. They regularly mark prominent gliding launch points, feeding sites, and nest entrances, creating a complex chemical landscape that provides information to other flying squirrels in the area.

Activity patterns follow strict nocturnal schedules, with emergence typically occurring 30-60 minutes after sunset and returning to dens before dawn. Peak activity occurs during the darkest hours of night, when their exceptional night vision provides maximum advantage over potential predators and competitors. Their soft fur enables nearly silent movement through the forest, allowing them to avoid detection by both predators and prey.

Territorial behaviors intensify during breeding season, with males expanding their ranges and engaging in more aggressive interactions with competitors. However, even during peak breeding periods, serious fights remain rare, with most conflicts resolved through vocal displays and intimidation rather than physical confrontation.

Social learning plays an important role in their behavioral development, with young individuals acquiring essential skills through observation and imitation of experienced adults. This cultural transmission of knowledge includes optimal gliding routes, seasonal food sources, and predator avoidance strategies that enhance survival rates across generations.

Interaction with Humans

The relationship between Southern Flying Squirrels and humans represents one of the more positive stories in North American wildlife conservation, characterized by their remarkable adaptability to human-modified landscapes and their generally beneficial impact on forest ecosystems. Unlike more conspicuous species such as the Eastern Gray Squirrel or Fox Squirrel that may sometimes conflict with human interests, Southern Flying Squirrels typically coexist peacefully with human neighbors due to their secretive nature and nocturnal habits.

Most human-flying squirrel encounters occur accidentally, often when homeowners discover family groups roosting in attics, barns, or other structures that provide suitable den sites. These discoveries frequently surprise property owners who had no idea that flying squirrels inhabited their area, highlighting how successfully these creatures maintain their secretive lifestyle even in suburban environments. Unlike other squirrel species that may cause significant structural damage, flying squirrels typically create minimal disturbance and rarely engage in destructive behaviors like extensive chewing or nest material gathering from insulation.

Their beneficial impacts on human environments often go unrecognized, as their nocturnal insect consumption provides valuable pest control services that can significantly reduce populations of moths, beetles, and other insects that might otherwise damage gardens, crops, or structures. A single flying squirrel family can consume thousands of insects annually, making them important allies in natural pest management strategies.

Suburban and rural environments that maintain sufficient tree cover often support thriving flying squirrel populations, with these adaptable creatures utilizing bird houses, nest boxes, and even decorative structures as den sites. Their presence in residential areas typically indicates healthy local ecosystems, as flying squirrels require continuous canopy cover and diverse food sources that benefit many other wildlife species.

Educational opportunities arise when people discover flying squirrels on their property, providing chances to learn about nocturnal wildlife and forest ecosystem functioning. Wildlife rehabilitators and nature centers often care for orphaned or injured flying squirrels, offering public education programs that help build appreciation for these remarkable creatures and their conservation needs.

Research activities continue to reveal new insights into flying squirrel ecology and behavior, with scientists using radio telemetry, nest box monitoring, and other techniques to study their habitat requirements and population dynamics. These studies inform forest management decisions and help identify conservation priorities across their range.

Climate change impacts remain less severe for Southern Flying Squirrels compared to their northern relatives, as their broad habitat tolerance and extensive range provide greater resilience to environmental changes. However, increasing temperatures and changing precipitation patterns may shift optimal habitat zones and affect food source availability in some regions.

Urban development continues to present challenges through habitat fragmentation and the creation of movement barriers that can isolate populations. However, their ability to utilize relatively small forest patches and their tolerance for human proximity makes them less vulnerable to development impacts than many other forest species.

Conservation Status and Threats

Southern Flying Squirrels enjoy relatively stable conservation status across most of their extensive range, with healthy populations persisting in both protected and unprotected forest environments throughout eastern North America. Their classification as a species of Least Concern reflects their adaptability to diverse habitat conditions and their demonstrated resilience to moderate levels of human disturbance, setting them apart from more specialized species that face greater conservation challenges.

However, this generally positive status masks regional variations and localized threats that warrant continued monitoring and targeted conservation efforts. Some peripheral populations, particularly those at the edges of their geographic range or in heavily fragmented landscapes, face pressures that could affect long-term viability and genetic diversity.

Habitat fragmentation represents the primary threat across much of their range, as development, agriculture, and forest management practices create increasingly isolated forest patches that limit movement and gene flow between populations. While Southern Flying Squirrels demonstrate greater tolerance for fragmentation than their northern relatives, extensive habitat loss can still reduce population density and increase vulnerability to local extinctions.

Forest management practices significantly influence population health and distribution patterns, with clear-cutting, selective harvesting, and plantation forestry creating habitat conditions that may not support optimal flying squirrel populations. The removal of mature trees eliminates essential den sites, while the reduction of canopy connectivity impedes movement and increases predation risk during ground travel.

Competition with other species presents localized challenges in some areas, particularly where Eastern Gray Squirrels have expanded their range or increased in density due to human activities. Gray squirrels may outcompete flying squirrels for prime den sites and food resources, particularly in edge habitats where both species overlap.

Climate change effects remain less pronounced than for northern species, though changing precipitation patterns and temperature regimes may affect food source availability and optimal habitat distribution. Extreme weather events, including severe storms and extended droughts, can impact population dynamics through direct mortality and reduced reproductive success.

Disease and parasite pressures represent emerging concerns, with some populations experiencing increased mortality from various pathogens that may be exacerbated by habitat stress and climate variability. Research continues to investigate the impacts of diseases on population dynamics and the potential for management interventions.

Predation pressure has increased in some areas due to changes in predator communities associated with human activities. Domestic cats represent a significant threat in suburban environments, while habitat modifications may increase exposure to raptors and other natural predators through reduced canopy cover.

Conservation efforts focus primarily on habitat protection and management, with emphasis on maintaining large blocks of connected forest and preserving mature forest characteristics including large trees, snags, and complex canopy structure. Many state wildlife agencies include Southern Flying Squirrels in forest management planning, ensuring that silvicultural practices consider their habitat needs alongside other forest species.

Protected areas play important roles in conservation, providing secure habitat where populations can persist without direct human interference. National and state forests, parks, and wildlife refuges across their range protect significant portions of their habitat and serve as source populations for recolonization of surrounding areas.

Research programs continue to monitor population trends, study habitat requirements, and investigate the impacts of various threats on population viability. Long-term datasets from nest box studies and other monitoring efforts provide valuable insights into population dynamics and conservation needs.

How to Help Southern Flying Squirrels

Supporting Southern Flying Squirrel conservation involves a combination of habitat management, citizen science participation, and public education efforts that address both local and landscape-level conservation needs. Whether you’re a property owner, wildlife enthusiast, or concerned citizen, numerous opportunities exist to contribute positively to the conservation of these remarkable creatures and the forest ecosystems they inhabit.

Habitat Creation and Management

Property owners can make significant contributions by maintaining and enhancing habitat suitability on their land. Install nest boxes specifically designed for flying squirrels, positioning them 8-15 feet high on tree trunks in areas with continuous canopy cover. These artificial den sites supplement natural cavities and provide secure breeding locations, particularly valuable in areas where mature trees with natural hollows are scarce.

Preserve existing mature trees whenever possible, as these provide essential den sites, food sources, and gliding launch points. Resist the urge to remove dead trees (snags) unless they pose immediate safety hazards, as these structures offer prime nesting opportunities and support the insects that form important dietary components for flying squirrels.

Create and maintain canopy corridors that connect forest patches, allowing flying squirrels to move safely between areas without requiring dangerous ground travel. Plant native trees and shrubs that provide food sources including nut-producing species like oaks and hickories, as well as fruit-bearing plants that support their diverse dietary needs.

Citizen Science and Monitoring

Participate in citizen science programs that monitor flying squirrel populations and distribution patterns. Many state wildlife agencies and research institutions rely on volunteers to help survey populations, maintain nest box programs, and document sightings. Your observations contribute valuable data that informs conservation planning and management decisions.

Report any flying squirrel sightings to local wildlife agencies, naturalist organizations, or online databases like iNaturalist. Every observation helps scientists understand current distribution patterns and population trends, particularly important for detecting range shifts or population changes over time.

Join or support nest box monitoring programs in your area, which provide valuable breeding habitat while generating important data on reproductive success, population density, and habitat preferences.

Wildlife-Friendly Practices

Implement yard and garden management practices that benefit flying squirrels and other wildlife. Reduce or eliminate the use of pesticides and herbicides that can poison flying squirrels directly or reduce their insect prey base. Choose native plants for landscaping projects, as these support the insects and produce the fruits and nuts that flying squirrels depend upon.

Keep cats indoors, especially during nighttime hours when flying squirrels are most active. Domestic cats represent a significant predation threat to flying squirrels and many other small mammals, particularly in suburban environments where natural predator-prey relationships may be disrupted.

Supporting Conservation Organizations

Donate to or volunteer with organizations working to protect forest habitats and conduct flying squirrel research. Many conservation groups, zoos, universities, and wildlife rehabilitation centers are actively involved in flying squirrel conservation efforts and depend on public support to continue their important work.

Support land trusts and conservation organizations that protect forest habitats within flying squirrel range, as habitat protection represents the most effective long-term conservation strategy for maintaining healthy populations.

Education and Outreach

Share your knowledge about flying squirrels with others, helping to build awareness and appreciation for these secretive creatures. Many people are amazed to learn that flying squirrels exist in North America and live in their local forests, making education efforts particularly impactful for building conservation support.

Participate in or organize night walks and wildlife viewing events that might offer opportunities to observe flying squirrels in their natural habitat. These experiences can create lasting connections between people and wildlife that translate into long-term conservation support.

Responsible Recreation

When recreating in flying squirrel habitat, follow Leave No Trace principles and avoid disturbing potential den sites or feeding areas. Time your activities to minimize disturbance during peak activity hours in the evening and early morning when flying squirrels are most likely to be active.

Use designated trails and camping areas to minimize habitat disruption, and educate fellow outdoor enthusiasts about the importance of protecting flying squirrel habitat and other forest wildlife.

Conclusion

The Southern Flying Squirrel stands as a testament to the remarkable adaptability and resilience that can emerge from millions of years of evolutionary refinement. These diminutive gliding mammals have successfully colonized an enormous range of forest habitats across eastern North America, demonstrating flexibility and ecological intelligence that has allowed them to thrive in environments ranging from pristine wilderness to suburban woodlots. Their success story offers hope and inspiration for wildlife conservation in an era of rapid environmental change.

Throughout this comprehensive exploration, we’ve discovered how Southern Flying Squirrels embody the perfect balance between specialization and adaptability. Their remarkable gliding abilities, sophisticated social behaviors, and diverse dietary strategies enable them to exploit ecological niches unavailable to other small mammals, while their flexibility allows them to persist in human-modified landscapes where more specialized species might disappear.

The conservation status of Southern Flying Squirrels reflects both their inherent resilience and the critical importance of maintaining forest connectivity across landscapes. While their populations remain generally stable, their continued success depends on our collective commitment to preserving the mature forests and habitat corridors that enable their aerial lifestyle. Understanding their needs, as detailed in our Complete North American Squirrel Species Guide, helps us appreciate how forest management decisions ripple through entire ecosystems.

Perhaps most importantly, Southern Flying Squirrels remind us that some of nature’s most extraordinary creatures may be living virtually invisible lives in our own backyards. Their secretive nature and nocturnal habits mean that thriving populations may exist undetected even in suburban environments, carrying out their essential ecological roles as seed dispersers, insect controllers, and forest health indicators while most human residents remain completely unaware of their presence.

The future of Southern Flying Squirrels appears more secure than that of many other forest species, yet their continued prosperity is not guaranteed. Climate change, habitat fragmentation, and intensifying human development pressures will require thoughtful management and continued vigilance to ensure that these aerial acrobats continue their nightly performances in North American forests for generations to come.

By supporting habitat conservation, participating in citizen science programs, and spreading awareness about these remarkable creatures, we can help ensure that the magic of flying squirrels continues to grace our forests. Every action we take to protect Southern Flying Squirrels also benefits the countless other species that share their woodland homes, from the towering oaks that serve as their highways to the intricate web of life that flourishes in healthy forest ecosystems.

The story of the Southern Flying Squirrel ultimately celebrates the incredible diversity and adaptability of life on Earth, reminding us that wonder and discovery await those who take time to explore the natural world around them, even if that exploration must wait for the cover of darkness when these gentle gliders begin their nightly dance through the trees.