The morning mist clings to the towering Douglas firs as you hike through the Pacific Northwest forest. A flash of silver-gray catches your eye – larger and more elusive than any squirrel you’ve seen before. This magnificent creature, pausing momentarily on a massive oak trunk, is the Western Gray Squirrel – one of North America’s most impressive and increasingly rare tree squirrels.

The Western Gray Squirrel (Sciurus griseus) is North America’s largest native tree squirrel, distinguished by its impressive size, brilliant silver-gray coat, and pure white underside. Endemic to the Pacific Coast region, this species faces significant conservation challenges due to habitat loss and competition from introduced Eastern Gray Squirrels.

| Attribute | Details |

|---|---|

| Scientific Name | Sciurus griseus |

| Size | 20-24 inches total length |

| Weight | 450-900 grams (1.0-2.0 lbs) |

| Lifespan | 7-8 years wild, up to 15 years maximum |

| Habitat | Oak woodlands, mixed conifer forests |

| Diet | Specialist: primarily acorns, pine nuts, fungi |

| Activity | Diurnal (most active morning and evening) |

| Conservation Status | Near Threatened (declining populations) |

Physical Description & Identification

General Appearance

Western Gray Squirrels command attention with their impressive size and striking appearance. As North America’s largest native tree squirrel, they dwarf their Eastern cousins and display a more robust, muscular build perfectly adapted for life in towering Pacific Coast forests.

Adult Western Gray Squirrels typically measure 20-24 inches from nose to tail tip, with their magnificent bushy tails accounting for nearly half their total length. Their substantial size becomes particularly apparent when compared to other western squirrel species, making identification relatively straightforward in their native range.

Coat Coloration and Seasonal Changes

Summer Coat (April-September): The Western Gray Squirrel’s summer pelage showcases their species’ most distinctive feature – a brilliant silver-gray dorsal coloration that appears almost metallic in bright sunlight. Individual guard hairs display banding patterns of white, gray, and black that create an iridescent quality unique among North American squirrels.

The striking contrast between their silver-gray backs and pristine white undersides provides one of the most reliable identification features. This sharp demarcation extends from chin to tail, creating a dramatic visual separation that distinguishes them from all other western squirrel species.

Winter Coat (October-March): Winter pelage grows considerably denser and longer, with increased guard hair length providing superior insulation against Pacific Northwest winters. The silver-gray coloration becomes slightly more muted but retains its characteristic metallic sheen.

Unlike Eastern Gray Squirrels, Western Gray Squirrels show minimal color variation across their range. Melanistic (black) individuals remain extremely rare, and albino specimens have never been documented in wild populations.

Distinguishing Features

Tail Characteristics:

- Exceptionally large and plume-like with silver-tipped guard hairs

- Length equals or exceeds body length (10-12 inches)

- Held in graceful arch over back when alert

- White-edged appearance from dorsal view

- Used extensively for balance during long leaps between trees

Facial Features:

- Large, dark eyes with prominent white eye-rings

- Longer snout compared to Eastern Gray Squirrels

- Prominent ear tufts during winter months

- Large, sensitive whiskers adapted for low-light navigation

- More angular facial profile than other squirrel species

Body Structure:

- Powerful hindquarters enable 15-foot horizontal leaps

- Exceptionally long, sharp claws for gripping massive tree trunks

- Flexible spine allows remarkable agility in canopy navigation

- Large body size provides advantages in territorial disputes

Habitat & Distribution

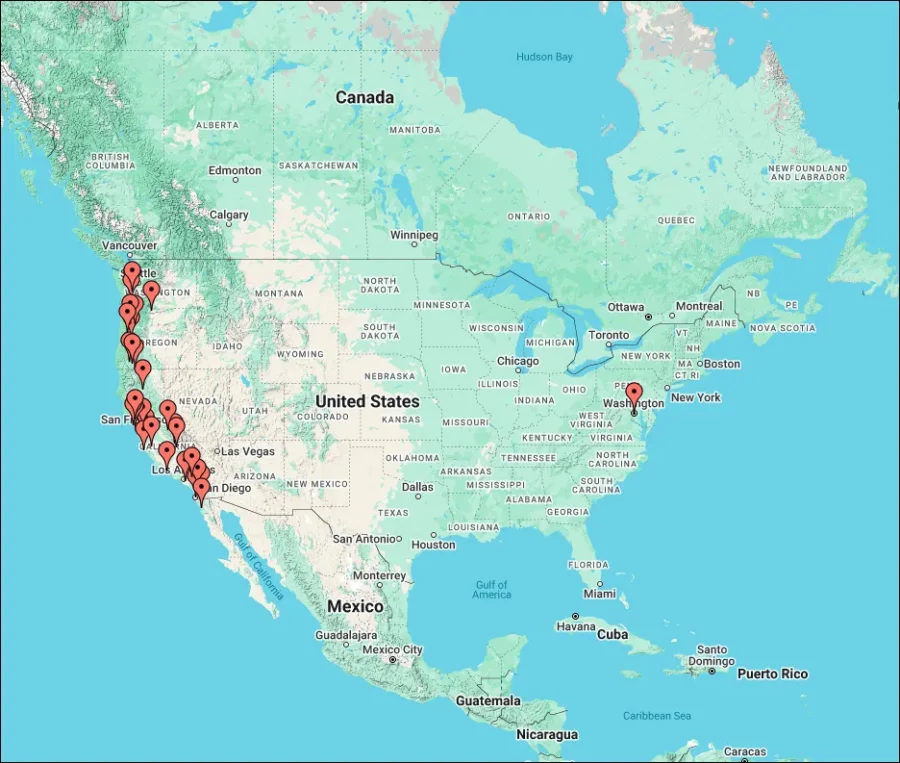

Native Range

Western Gray Squirrels occupy a narrow but ecologically diverse range along North America’s Pacific Coast. Their distribution extends from Washington State through Oregon and California, with isolated populations in Baja California, Mexico.

This endemic species evolved in the unique ecosystems of the Pacific Coast, where Mediterranean-type climates support distinctive plant communities dominated by oak woodlands and mixed conifer forests. Their specialized habitat requirements make them particularly vulnerable to environmental changes and habitat fragmentation.

Optimal Habitat Requirements:

- Mature oak woodlands with 40% or greater canopy coverage

- Mixed conifer forests containing Douglas fir, ponderosa pine, and sugar pine

- Elevation ranges from sea level to 6,000 feet

- Annual precipitation between 15-60 inches

- Tree diversity supporting year-round food availability

- Natural cavities in mature trees for nesting

Geographic Distribution

Northern Range (Washington State): Western Gray Squirrels reach their northernmost distribution in south Puget Sound region and scattered locations throughout southwestern Washington. These populations represent the species’ most isolated communities and face particular conservation challenges.

Central Range (Oregon): Oregon supports the most stable Western Gray Squirrel populations, particularly in the Cascade Range foothills and Willamette Valley oak woodlands. The state’s diverse forest ecosystems provide optimal habitat conditions across multiple elevation zones.

Southern Range (California): California contains the vast majority of remaining Western Gray Squirrel habitat, from coastal ranges through the Sierra Nevada mountains. However, even California populations face significant pressure from urban development and habitat conversion.

Habitat Preferences and Ecosystem Requirements

Oak Woodland Specialists: Western Gray Squirrels demonstrate strong preferences for mature oak woodlands, particularly those dominated by valley oaks, blue oaks, and coast live oaks. These ecosystems provide both primary food sources and essential nesting cavities.

Mixed Conifer Associations: In mountainous regions, Western Gray Squirrels thrive in mixed conifer forests where sugar pine, ponderosa pine, and Douglas fir create diverse canopy structure and varied food resources throughout the year.

Elevation and Climate Adaptations: Unlike many squirrel species, Western Gray Squirrels show remarkable adaptability across elevation gradients, occupying habitats from coastal fog zones to montane forests above 5,000 feet elevation.

Edge Habitat Utilization: Western Gray Squirrels frequently utilize ecotone areas where oak woodlands transition to conifer forests or grasslands, taking advantage of increased habitat diversity and food resource availability.

Diet & Feeding Behavior

Seasonal Dietary Specialization

Western Gray Squirrels demonstrate more specialized feeding behaviors than their eastern relatives, with pronounced seasonal dietary shifts reflecting their dependence on specific Pacific Coast ecosystems.

Spring Diet (March-May):

- Oak catkins and newly emerged leaves

- Fresh shoots from preferred tree species

- Early wildflowers and tender vegetation

- Cached acorns from previous autumn harvest

- Tree sap accessed through bark gnawing

- Occasional bird eggs during peak nesting season

Summer Diet (June-August):

- Green oak leaves and terminal shoots

- Developing acorns and other early nuts

- Native berries including manzanita and elderberry

- Fungi and mushrooms, particularly chanterelles

- Insects and larvae (minimal protein supplementation)

- Water-rich vegetation during dry periods

Autumn Diet (September-November):

- Primary focus: acorn collection and storage

- Pine nuts from sugar pine, ponderosa pine, and Douglas fir

- Late-season berries and fruits

- Increased caloric intake preparing for winter scarcity

- Intensive caching behavior dominating daily activities

Winter Diet (December-February):

- Heavy reliance on cached acorn reserves

- Inner bark (cambium) from preferred tree species

- Remaining nuts and stored food items

- Limited fresh vegetation during dormant season

- Occasional opportunistic feeding on available resources

Acorn Specialization and Processing

Western Gray Squirrels have evolved sophisticated adaptations for processing and storing acorns, their primary food source throughout much of their range.

Acorn Selection Criteria:

- Species preference: Valley oak and blue oak acorns preferred over others

- Quality assessment: Ability to detect insect damage and tannin levels

- Size selection: Preference for larger acorns with higher caloric content

- Timing: Harvesting acorns at optimal ripeness for storage longevity

Processing Techniques:

- Shell removal: Specialized gnawing patterns for efficient access

- Tannin reduction: Burial in moist soil reduces bitter compounds

- Quality sorting: Immediate consumption of damaged nuts, storage of perfect specimens

- Cache preparation: Removal of caps and cleaning before burial

Caching Behavior and Territory Management

Western Gray Squirrels employ more sophisticated caching strategies than most other squirrel species, reflecting their dependence on stored food for winter survival.

Cache Distribution Patterns:

- Scatter hoarding: Individual nuts buried throughout large territories

- Territorial caching: Cache sites concentrated within defended areas

- Elevation preferences: Higher elevation sites preferred for longer storage

- Microhabitat selection: Well-drained soils with appropriate moisture levels

Memory and Retrieval Systems:

- Spatial memory: Exceptional ability to relocate thousands of cache sites

- Seasonal timing: Systematic retrieval based on burial dates and food quality

- Territory familiarity: Intimate knowledge of landscape features and landmarks

- Recovery efficiency: Successful retrieval of approximately 80% of cached items

Cache Protection Behaviors:

- False caching: Deceptive burial behavior when observed by competitors

- Site concealment: Careful covering and camouflage of cache locations

- Multiple visits: Checking and maintaining cache sites throughout winter

- Theft prevention: Aggressive defense of cache areas from intruders

Reproduction & Life Cycle

Breeding Season and Reproductive Timing

Western Gray Squirrels typically experience a single annual breeding season, unlike many other squirrel species that may breed twice yearly. This reproductive strategy reflects their adaptation to Pacific Coast climates and seasonal resource availability.

Primary Breeding Season (December-March): Winter breeding ensures that offspring are born during favorable spring conditions when food resources become increasingly available and weather patterns stabilize.

Breeding Timing Variations:

- Northern populations: Later breeding (February-March) due to extended winters

- Southern populations: Earlier breeding (December-January) in milder climates

- Elevation effects: Higher elevation populations delay breeding based on snowpack

- Resource availability: Abundant acorn crops may trigger earlier breeding

Courtship and Mating Behavior

Western Gray Squirrel courtship involves elaborate displays and intense male competition, with behaviors adapted to their large territories and low population densities.

Pre-Mating Behaviors:

- Long-distance chasing: Males pursue females across extensive territories

- Vocal displays: Complex vocalizations advertising male quality and availability

- Scent marking: Intensive marking of territorial boundaries and travel routes

- Aggressive interactions: Males establish dominance hierarchies through confrontation

Mating Process: Female Western Gray Squirrels typically mate with multiple males during their brief receptive period, which lasts 12-18 hours. This polyandrous system ensures genetic diversity while allowing females to select the highest-quality mates.

Pregnancy and Nest Construction

Gestation Period: 42-46 days

Nest Site Selection: Pregnant females invest considerable effort in selecting and preparing secure nest sites, with cavity availability often limiting reproductive success in degraded habitats.

Preferred Nest Types:

- Natural tree cavities: Hollow sections in mature oaks, pines, or firs

- Woodpecker holes: Enlarged cavities originally created by large woodpeckers

- Leaf nests: External structures built in dense foliage during cavity shortages

- Cliff crevices: Rocky outcrop shelters in areas with limited tree cavities

Nest Characteristics:

- Size: Larger than Eastern Gray Squirrel nests due to increased body size

- Insulation: Extensive use of bark strips, moss, and soft plant materials

- Multiple entrances: Emergency escape routes essential for predator avoidance

- Height placement: Typically 25-60 feet above ground for maximum security

Offspring Development and Maternal Care

Birth Characteristics: Western Gray Squirrel litters typically contain 2-4 young, born after the 42-46 day gestation period.

Newborn Features:

- Size: Approximately 4 inches long, weighing 15-20 grams

- Appearance: Pink, hairless, with closed eyes and ears

- Development: Slower maturation compared to smaller squirrel species

Developmental Timeline:

Weeks 1-3:

- Rapid growth through rich maternal milk

- Complete dependence on mother for thermoregulation

- First silver-gray fur development begins

Weeks 4-5:

- Eyes open around day 32-35

- Ears become functional around day 35

- Initial coordination and balance development

Weeks 6-7:

- First ventures outside nest cavity

- Beginning of solid food introduction

- Maternal instruction in basic foraging techniques

Weeks 8-10:

- Gradual weaning from maternal milk

- Increased independence in daily activities

- Learning advanced foraging and caching behaviors

Weeks 11-12:

- Full independence from mother

- Establishment of individual territories

- Adult behavioral patterns and social interactions

Extended Maternal Investment: Western Gray Squirrel mothers provide longer parental care compared to other squirrel species, with some young remaining in maternal territories through their first winter.

Behavior & Social Structure

Daily Activity Patterns and Seasonal Variations

Western Gray Squirrels exhibit distinct activity patterns that vary significantly based on season, weather conditions, and resource availability.

Dawn Activity (Sunrise + 30 minutes – 2 hours): Early morning represents the most intensive activity period, when squirrels emerge from overnight shelters to assess territorial conditions and locate food sources. Cool temperatures and reduced predator activity make dawn optimal for extensive foraging.

Midday Behavior (Late Morning – Early Afternoon): During peak daylight hours, Western Gray Squirrels often retreat to shaded resting areas or tree cavities. This behavior becomes particularly pronounced during hot summer weather or winter storms.

Evening Activity (2-3 hours before sunset): Late afternoon and early evening see renewed intensive activity, with focus on final foraging opportunities and cache maintenance. Autumn evenings feature particularly intense acorn collection and burial behaviors.

Seasonal Activity Modifications:

- Winter: Significantly reduced activity during storms and extreme cold

- Spring: Extended dawn activity periods during breeding and territorial establishment

- Summer: Earlier morning activity to avoid afternoon heat stress

- Autumn: Longest activity periods driven by intensive caching requirements

Communication and Social Interactions

Western Gray Squirrels possess complex communication systems adapted to their large territories and relatively low population densities.

Vocal Communication Repertoire:

Alarm Calls:

- Chuck-calls: Rapid-fire warnings for ground-based predators

- Bark-calls: Loud, penetrating alerts for aerial threats

- Whistle-calls: Long-distance warnings spanning large territories

Social Vocalizations:

- Contact calls: Soft sounds maintaining family group cohesion

- Territorial calls: Long-distance advertisements of territory ownership

- Mating calls: Complex vocalizations during breeding season

Visual Display Behaviors:

Tail Signaling:

- Flagging: Dramatic tail movements indicating alarm or territorial assertion

- Arching: Tail positioning demonstrating dominance or aggressive intent

- Wrapping: Defensive posture during submissive interactions

Body Language:

- Upright alertness: Maximum vigilance posture for threat assessment

- Flattened concealment: Cryptic positioning for predator avoidance

- Aggressive displays: Lunging, chasing, and mock attack behaviors

Territorial Behavior and Range Management

Western Gray Squirrels maintain some of the largest territories among North American tree squirrels, reflecting their specialized habitat requirements and resource distribution patterns.

Territory Characteristics:

- Size: 5-15 acres depending on habitat quality and resource density

- Shape: Often elongated along ridge lines or creek corridors

- Seasonal variation: Territory size increases during autumn caching period

- Defense intensity: Vigorous defense of core areas around nest sites and primary caches

Territorial Marking and Maintenance:

- Scent marking: Strategic placement of chemical signals at territory boundaries

- Visual markers: Claw marks and gnaw signs on prominent trees

- Vocal advertisements: Regular calling from elevated perches

- Physical patrols: Daily inspection of territorial boundaries

Resource Territory Management:

- Cache site protection: Intensive defense of primary food storage areas

- Nesting territory: Absolute exclusion of competitors from breeding areas

- Foraging ranges: Shared access to abundant seasonal resources

- Travel corridors: Maintenance of safe passage routes between territory sections

Social Hierarchy and Competitive Interactions

Despite their generally solitary nature, Western Gray Squirrels maintain complex social relationships that influence resource access and reproductive success.

Dominance Factors:

- Body size: Larger individuals typically dominate smaller competitors

- Territory quality: Residents with superior habitat hold higher status

- Age and experience: Older squirrels command respect from younger individuals

- Reproductive condition: Breeding females receive enhanced deference

Competitive Interactions:

- Resource competition: Aggressive defense of high-quality food sources

- Nest site disputes: Intense competition for optimal cavity locations

- Cache protection: Surveillance and defense against food theft

- Territorial boundaries: Regular confrontations over range limits

Conservation Status and Threats

Population Assessment and Current Status

Western Gray Squirrels face significant conservation challenges throughout their range, with populations declining substantially over the past several decades. Current estimates suggest range-wide population reductions of 30-60% since the 1980s.

Population Status by Region:

- Washington State: Critically low populations, potential extirpation risk

- Oregon: Stable populations in core habitat areas, declining in marginal habitats

- Northern California: Moderate populations with ongoing habitat pressure

- Central/Southern California: Most stable populations but facing urban development pressure

Conservation Classification:

- Overall Status: Near Threatened with declining trend

- State Classifications: Threatened species listing in Washington State

- Regional Concern: Species of Special Concern in California and Oregon

- Habitat Protection: Listed as sensitive species requiring habitat conservation

Primary Threats and Conservation Challenges

Habitat Loss and Fragmentation: Urban and agricultural development represents the most significant threat to Western Gray Squirrel populations. Conversion of oak woodlands and mixed forests eliminates essential habitat while fragmenting remaining populations.

Habitat Degradation Factors:

- Oak woodland conversion: Agricultural and residential development

- Forest management practices: Removal of large, cavity-containing trees

- Fire suppression: Alteration of natural forest structure and composition

- Invasive plant species: Competition with native vegetation

Competition from Eastern Gray Squirrels: Introduced Eastern Gray Squirrels pose a significant threat to native Western Gray Squirrel populations through direct competition and potential disease transmission.

Competitive Disadvantages:

- Reproductive rate: Eastern Gray Squirrels breed twice yearly versus once for Western Gray Squirrels

- Habitat flexibility: Eastern Gray Squirrels adapt more readily to disturbed habitats

- Resource competition: Overlap in food preferences creates direct competition

- Disease transmission: Potential for novel pathogen introduction

Climate Change Impacts: Shifting precipitation patterns and increasing temperatures affect food availability and habitat suitability across the Western Gray Squirrel’s range.

Climate-Related Concerns:

- Drought stress: Reduced acorn production during extended dry periods

- Fire regime changes: Increased wildfire frequency and intensity

- Temperature extremes: Heat stress and altered seasonal activity patterns

- Precipitation shifts: Changes in oak woodland productivity and regeneration

Disease and Health Threats: While less studied than in other squirrel species, Western Gray Squirrels face potential health challenges that could impact population stability.

Health Risk Factors:

- Squirrelpox virus: Potential introduction through contact with Eastern Gray Squirrels

- Parasitic infections: Mites, fleas, and internal parasites in degraded habitats

- Nutritional stress: Reduced habitat quality leading to compromised immune systems

- Environmental contaminants: Pesticide exposure in agricultural areas

Conservation Efforts and Management Strategies

Habitat Protection and Restoration:

- Oak woodland preservation: Protection of existing mature oak habitats

- Reforestation programs: Planting native tree species in degraded areas

- Connectivity restoration: Creating wildlife corridors linking fragmented habitats

- Fire management: Restoring natural fire regimes to maintain habitat structure

Research and Monitoring Programs:

- Population surveys: Regular monitoring of population density and distribution

- Habitat assessment: Evaluation of habitat quality and carrying capacity

- Genetic studies: Assessment of population connectivity and genetic diversity

- Behavioral research: Understanding habitat requirements and adaptation strategies

Species Management:

- Eastern Gray Squirrel control: Removal programs in sensitive Western Gray Squirrel habitats

- Nest box programs: Provision of artificial cavities in habitat restoration areas

- Translocation efforts: Moving individuals from development areas to protected habitats

- Captive breeding: Emergency population maintenance in case of severe declines

How to Help Western Gray Squirrels

Creating and Maintaining Squirrel-Friendly Habitats

Individual landowners within the Western Gray Squirrel’s range can take significant actions to support conservation efforts while contributing to species recovery.

Native Plant Landscaping:

Oak Species Selection:

- Valley oak (Quercus lobata): Primary food source in suitable climates

- Blue oak (Quercus douglasii): Excellent for foothill and inland areas

- Coast live oak (Quercus agrifolia): Ideal for coastal and near-coastal regions

- Oregon white oak (Quercus garryana): Essential for northern range populations

Conifer Integration:

- Sugar pine (Pinus lambertiana): Valuable nut source in appropriate elevations

- Ponderosa pine (Pinus ponderosa): Important habitat structure and food source

- Douglas fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii): Essential canopy and nesting habitat

- Incense cedar (Calocedrus decurrens): Valuable for habitat diversity

Understory Management:

- Native shrub preservation: Maintain manzanita, ceanothus, and elderberry

- Invasive species control: Remove non-native plants competing with oak regeneration

- Natural succession: Allow natural forest regeneration in appropriate areas

- Fire-adapted landscaping: Utilize native plants adapted to natural fire cycles

Property Management for Western Gray Squirrel Conservation

Tree Conservation Practices:

- Preserve mature trees: Protect existing large oaks and conifers with potential cavities

- Snag retention: Maintain dead trees that provide nesting opportunities when safe

- Pruning guidelines: Minimize pruning during breeding season (December-May)

- Chemical-free management: Avoid pesticides and herbicides that affect food webs

Water Resource Management:

- Natural water sources: Maintain or create small ponds and seasonal water features

- Drought adaptation: Provide supplemental water during extended dry periods

- Drainage considerations: Ensure proper drainage around oak root zones

- Riparian protection: Preserve and restore creek corridors and spring areas

Cavity and Nesting Support:

- Nest box installation: Large wooden boxes designed specifically for Western Gray Squirrels

- Cavity preservation: Protect trees with natural hollows from removal

- Artificial cavities: Commission woodworkers to create species-appropriate nest boxes

- Cavity maintenance: Regular inspection and cleaning of artificial nest structures

Reducing Human-Wildlife Conflicts

Property Protection Strategies:

Humane Exclusion Methods:

- Hardware cloth barriers: 1/4-inch mesh over vulnerable structures

- Tree guards: Smooth metal barriers preventing building access

- Roof protection: Secure all potential entry points larger than 3 inches

- Garden protection: Row covers and mesh protection for vulnerable plants

Coexistence Strategies:

- Feeding guidelines: Appropriate native food supplementation if necessary

- Observation protocols: Responsible wildlife watching that minimizes disturbance

- Pet management: Controlling domestic cats and dogs in squirrel habitat areas

- Noise reduction: Minimizing disturbance during breeding and nesting seasons

Supporting Conservation Research and Monitoring

Citizen Science Participation:

- Population monitoring: Participate in annual Western Gray Squirrel surveys

- Habitat assessment: Document habitat conditions and changes over time

- Behavioral observations: Report unusual behaviors or population changes

- Distribution mapping: Contribute sighting data to conservation databases

Research Support:

- University partnerships: Support graduate student research on Western Gray Squirrels

- Funding contributions: Donate to conservation organizations working on species recovery

- Habitat donation: Consider conservation easements on important squirrel habitats

- Educational outreach: Share knowledge about Western Gray Squirrel conservation needs

Volunteer Opportunities:

- Habitat restoration: Participate in oak woodland planting and maintenance projects

- Eastern Gray Squirrel monitoring: Assist with removal programs in sensitive areas

- Public education: Help educate others about Western Gray Squirrel conservation

- Data collection: Assist researchers with field work and monitoring efforts

Political and Policy Support

Conservation Advocacy:

- Land use planning: Advocate for Western Gray Squirrel habitat protection in development decisions

- Species legislation: Support stronger protections for Western Gray Squirrels

- Funding support: Advocate for increased conservation funding at state and federal levels

- Habitat connectivity: Support wildlife corridor development and protection

Local Government Engagement:

- Planning commission participation: Attend meetings addressing habitat conservation

- Environmental review: Comment on development projects affecting squirrel habitat

- Policy development: Work with local governments to develop squirrel-friendly policies

- Education initiatives: Support environmental education programs in schools

Conclusion

The Western Gray Squirrel represents both the beauty and fragility of Pacific Coast ecosystems. As North America’s largest native tree squirrel, this magnificent species embodies the unique evolutionary heritage of western forests while facing unprecedented challenges in an increasingly developed landscape.

Understanding Western Gray Squirrel ecology reveals the intricate connections between species conservation and ecosystem health. Their dependence on mature oak woodlands and old-growth forest features makes them excellent indicators of habitat quality while highlighting the importance of protecting these increasingly rare ecosystems.

Conservation success for Western Gray Squirrels requires coordinated efforts across multiple scales – from individual property owners creating squirrel-friendly landscapes to regional habitat protection and restoration programs. Through habitat preservation, invasive species management, and public education, we can work to ensure that future generations will continue to witness these remarkable animals in their native Pacific Coast forests.

The Western Gray Squirrel’s story serves as a compelling reminder that wildlife conservation often depends on protecting entire ecosystems rather than managing individual species in isolation. By supporting oak woodland conservation and old-growth forest protection, we contribute to maintaining the biodiversity and ecological integrity that sustains not only Western Gray Squirrels but countless other native species.

Whether observing their impressive acrobatic abilities among towering trees, marveling at their sophisticated caching behaviors, or simply appreciating their role in forest ecosystem dynamics, Western Gray Squirrels offer profound opportunities for connecting with the natural heritage of western North America. Their conservation represents our commitment to preserving the wild landscapes and native species that define the Pacific Coast’s natural character.